The foods we eat do more than just provide energy and nutrients; they’re in a constant, delicate dance with our immune system. A new study suggests that common food proteins, specifically those found in milk, may be a secret weapon against certain types of cancer. Researchers found that these proteins, which are often mistakenly seen as potential allergens, could be actively triggering a tumor-fighting response in our gut, specifically in the small intestine. This discovery challenges what we thought we knew about the constant battle our bodies fight to stay healthy.

This groundbreaking research, led by Dr. Hiroshi Ohno at the RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences in Japan, connects food antigens—the parts of food that our immune system reacts to—with the suppression of tumors in the small intestine. The small intestine is a crucial but often overlooked area when it comes to cancer, and early detection is particularly difficult.

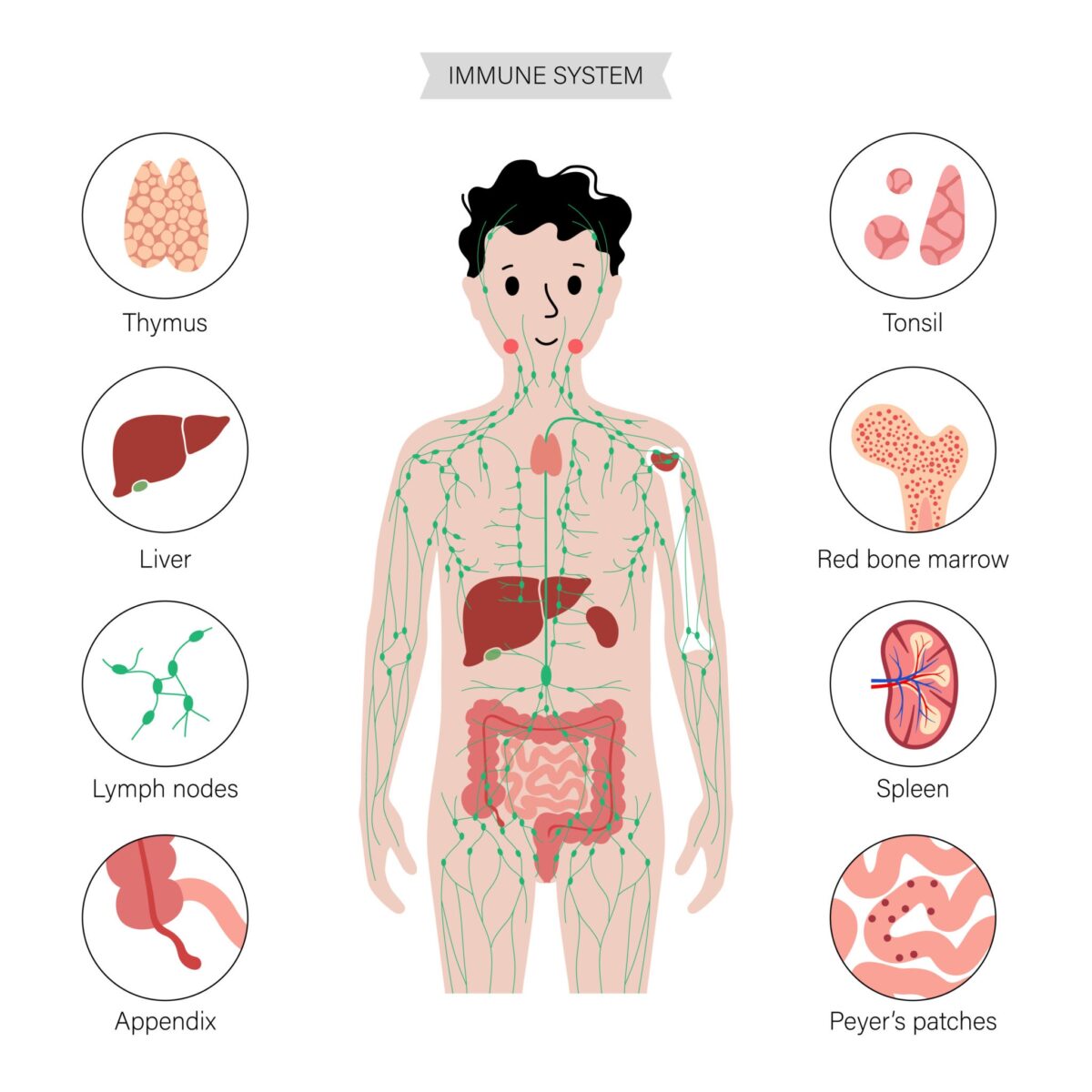

To truly grasp the significance of this, it helps to understand what’s happening inside our gut. The small intestine is lined with specialized immune tissues called Peyer’s patches, which act as a kind of lookout post. They contain unique doorways, known as M cells, which allow small bits of food proteins to enter so that immune cells can inspect them. This process is key to keeping the gut healthy and teaching the immune system what is safe and what is a threat.

It had been known that food antigens could activate immune cells in the small intestine. But the specific link between these antigens and tumor suppression had remained a mystery until now. The Ohno team’s work reveals that the antigens from our food are the spark that ignites this protective response within the Peyer’s patches.

The Study: What Happens When We Remove Antigens?

To investigate this theory, the researchers used a specific type of mouse, the Apcmin/+ mouse, a common model for intestinal tumor development. These mice have a genetic mutation that makes them prone to developing multiple tumors in their small and large intestines.

The initial experiment involved putting a group of these mice on a special antigen-free diet, which lacked any food proteins that the immune system would recognize. After six weeks, the researchers observed a dramatic increase in the number of tumors in the small intestines of these mice compared to a control group on a normal diet. Interestingly, the number of tumors in their large intestine was unchanged. This finding strongly implied that something in the normal diet was actively preventing tumor growth in the small intestine.

To confirm that it was indeed the food antigens causing this effect, the researchers added a common food antigen—bovine serum albumin (BSA), a protein found in milk—back into the antigen-free diet. The mice that received this fortified diet saw their small intestinal tumor counts drop back to normal levels. This finding provided strong evidence that food antigens were directly responsible for suppressing the tumors.

To dig deeper into the “how” of this process, the team looked at the immune cells themselves. They observed that the mice on the antigen-free diet had a significant decrease in T cells in their small intestines. This pointed to the immune system as the key player. The researchers then used mice that were genetically engineered to lack Peyer’s patches. In these mice, even on a normal diet, the number of small intestinal tumors increased to levels similar to the mice on the antigen-free diet. This demonstrated that Peyer’s patches are essential for this tumor-suppressing mechanism.

The study concluded that food antigens influence a type of T cell called a Th1 cell, which is known to produce a molecule called interferon-gamma (IFNγ). This molecule has been shown to suppress tumor growth, providing a potential explanation for the protective effect observed.

A New Perspective on Diet and Health

This research highlights that our diet is more than just fuel; it’s in a constant, profound interaction with our immune system. The food proteins we consume aren’t just potential allergens or foreign invaders. They appear to be active participants in our immune health, helping our body defend itself against cancer.

While these findings are based on a mouse study and more research is needed, this work opens up a new avenue for understanding how our diet can influence our immune system and, in turn, our health. It could lead to a new wave of research on how specific food components might be used to help prevent certain types of cancer. Our diet and our immune system are deeply intertwined, and what we eat could be one of our most powerful defenses.

Paper Summary

Methodology

The researchers used Apcmin/+ mice, a model for intestinal tumorigenesis, to study the role of food antigens. They fed these mice a laboratory-made antigen-free diet (AFD) for six weeks and compared the number of small intestinal tumors to mice on a normal chow diet (NCD). To confirm that the food antigens were the key factor, they added bovine serum albumin (BSA), a model food antigen, back into the AFD and observed the effects on tumor growth. They also studied mice that were genetically engineered to lack Peyer’s patches (PPs), the immune-inductive sites in the small intestine, to understand the role of this tissue in tumor suppression. The number and size of tumors were measured, and the immune cells were analyzed using flow cytometry and single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis. The study used both male and female mice in the Apcmin/+ mouse experiments and M-cell null mouse experiments, but only female mice were used in the PP-null experiments.

Results

The study found that Apcmin/+ mice on an antigen-free diet had a significantly higher number of small intestinal tumors compared to mice on a normal diet. This increase in tumors was associated with a decrease in T cells in the small intestine. When bovine serum albumin (a food antigen from milk) was added back into the antigen-free diet, the number of small intestinal tumors and T cells were restored to normal levels. Furthermore, mice that lacked Peyer’s patches also showed an increased number of small intestinal tumors, confirming the critical role of these immune tissues in tumor suppression. The researchers concluded that food antigens play a crucial role in suppressing small intestinal tumors by inducing immune cells, particularly Th1 cells, through the Peyer’s patches.

Limitations

The study was conducted using a mouse model, and further research would be needed to confirm these findings in humans. The study also used specific model antigens (BSA and OVA), and it is not certain if the effect is universal for all food antigens or specific to certain types of proteins. The study also mentions that while they used both male and female mice in some experiments, only female mice were used in the PP-null experiment.

Funding or Disclosures

The paper is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The authors are affiliated with institutions including the RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences in Japan and Yokohama City University.

Paper Publication Info

The study, titled “Food antigens suppress small intestinal tumorigenesis,” was published on September 18, 2024, in the scientific journal Frontiers in Immunology. The DOI for the paper is 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1373766.