It’s no secret that the gut bacteria plays a role in just about every part of our health makeup, from digestion to mental health. At the same time, having a variety of certain kinds of bacteria may make us more prone to disease. A new study from the University of Chicago reports that commensal bacteria encourage leukemia caused by the murine leukemia virus (MuLV) by suppressing the anti-tumor immune response in mice.

In 1910, pathologist Peyton Rous took a malignant tumor sample from one chicken and injected it into another, which induced cancer in it. At the time, researchers didn’t take this finding seriously, but later it was revealed that the cancer was able to transfer between birds through retroviral transmission. It was from this point that scientists began cracking down on the discovery, with studies continuing to link several retroviruses to cancer.

A 2011 study conducted by the senior author of this current study, Tatyana Golovkina, PhD, reveals that a virus that causes mammary tumors in mice is dependent upon the gut microbiome. Certain bacteria was able to provide the virus with a clear path of infection by allowing it to block immune cells from recognizing the infected cells. Ultimately, this led to tumor development as the microbes allowed the virus to replicate uninterrupted.

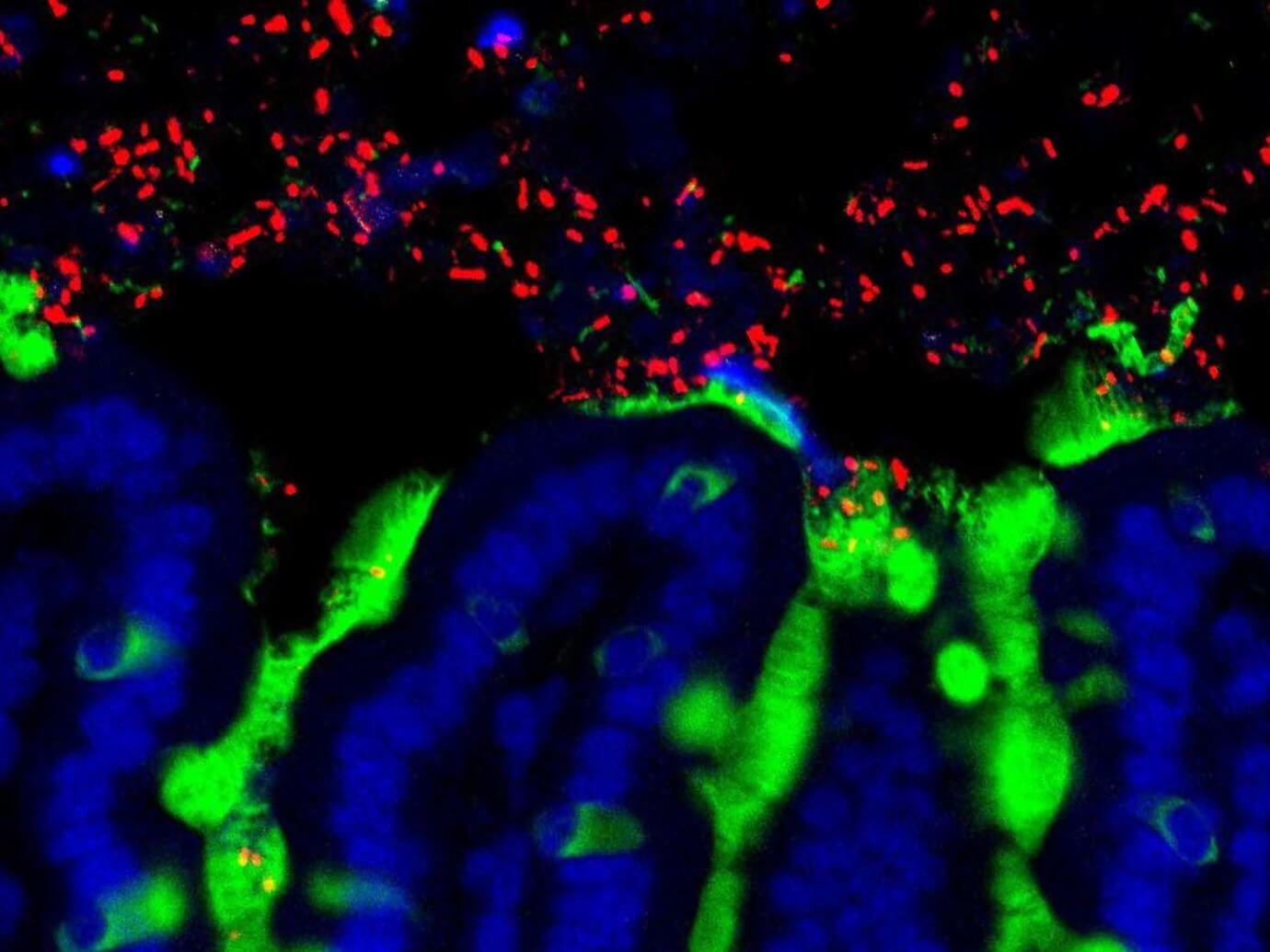

Fast forward to now, Golovkina and her team wanted to examine the effect that commensal bacteria had on a virus-induced cancer in any other possible way other than promoting replication. To do this, they used germ-free (GF) mice with no microbes that had been raised in a special facility, and specific pathogen free (SPF) mice that had commensal microbes that normally are in the gut lining, but no pathogenic ones. Both mice were then infected with the murine leukemia virus (MuLV). While the virus infected and replicated consistently in both types, only SPF mice developed tumors.

With this in mind, the team then explored what could be causing the gut to miss this pathogenic invasion and allow the cancer to spread about easily, surviving enough to promote a tumor. They conducted a series of experiments with immunodeficient mice that were engineered to be without an immune system.

In the germ-free setting, these mice developed tumors when exposed to the virus in the same way as SPF mice with intact adaptive immune systems. This suggests that the typical immune response is blocked by the virus due to gut microbes acting against it, helping the pathogens rather than the body.

Researchers ultimately found that the commensal bacteria responsible gives rise to three genes that would typically cause the immune system to shut off in response to pathogen exposure rather than allow it to roam. Two of the genes, Serpinb9b and Rnf128, are also well-studied indicators of poor prognosis for humans suffering from more randomly onset cancers.

“These two negative immune regulators have been really well documented to be poor prognostic factors in some human cancers, but nobody knew why,” says Golovkina in a university release. “Using a mouse model of leukemia, we found that the bacteria contribute to upregulation of these negative immune regulators, allowing developing tumors to escape recognition by the immune system.”

Future directions for the team involve figuring out why the immune system is suppressed only when the retrovirus and gut bacteria are both present. “Now we have to figure out what’s so special about bacteria which have these properties,” Golovkina concludes.

This study is published in the journal Cell Reports.