T cells are a double-edged sword when it comes to colorectal cancer. Researchers from The Rockefeller University reveal these intestinal white blood cells first rein in early-stage tumors. When the cancer begins to progress, however, these cells undergo biochemical changes and end up strengthening the tumor.

“T cells that live in the gut act to prevent tumor formation. But once tumors form, gut T cell populations change, enter the tumor and promote tumor growth,” says Bernardo Reis, a research associate in Daniel Mucida’s laboratory at The Rockefeller University, in a university release.

The intestinal lining consists of a single layer of epithelial cells, absorbing useful substances and rejecting harmful ones. Researchers say T cells mind the gaps within the intestinal lining, scanning the epithelium to maintain the integrity and prevent pathogens from invading the rest of the body.

Reis wanted to investigate the conflicting claims of whether T cells helped or stopped the growth of intestinal tumors. He found there was no simple answer.

“We had data showing T cells were protective, but the literature suggested that they also promote tumor growth,” explains Reis. “We wanted to understand what these T cells were really up to.”

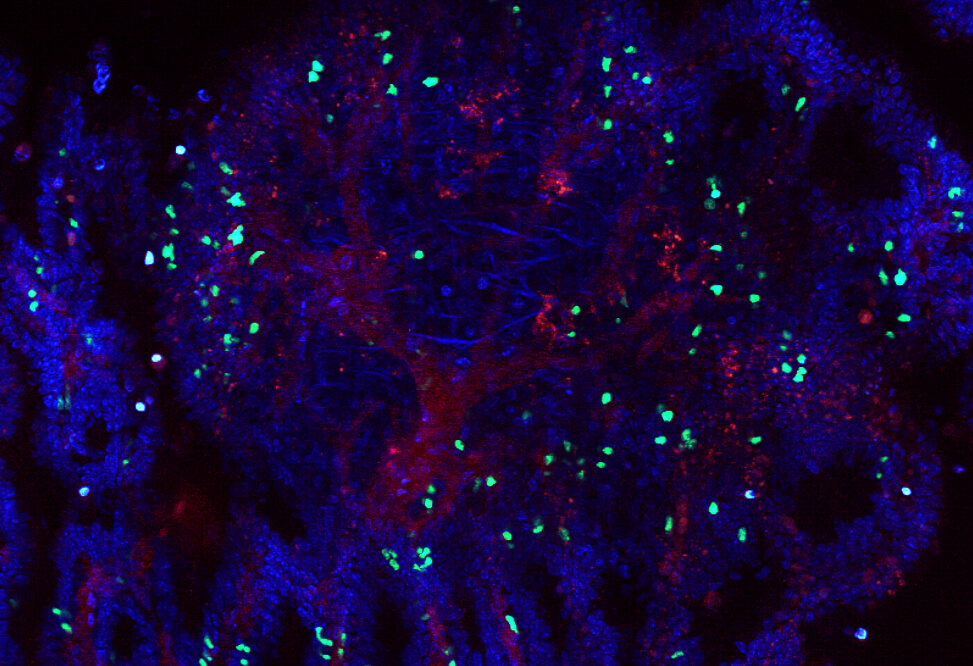

Using a mouse model, researchers obtained T cells from animal intestines with early-stage tumors and from the tumors of mice with advanced cancer. Researchers were astonished to find extensive molecular differences while comparing the two sources of supposedly identical cells. They discovered that two categories of T cells boasted different T cell receptors. Researchers also found that T cells had entered a tumor-produced cytokine that promotes inflammation in response to infection, known as IL-17.

Study authors detected that IL-17 was promoting cancer in the tumor microenvironment. It was spurring tumor growth and recruiting other cells to help hide the tumor from the rest of the immune system.

“The T cells had completely changed,” explains Reis.

Researchers then used CRISPR gene editing technology to remove T cell receptors from the white blood cells, changing the cells from anti-tumor to pro-tumor, or vice versa. Within the mouse models, researchers were able to increase the number and decrease the size of tumors. “When we depleted the original T cells, the mice became sicker,” says Reis. “And when we depleted the tumor-invading T cells, the tumors shrank.”

Researchers also observed similar activity in T cells acquired from human colorectal tumors and their environs. “It almost looked like a fight between these two populations,” says Reis. “Regular cells were trying to contain the tumor while cells inside were promoting tumor growth.”

Future studies will examine whether it might be possible to modulate normal T cells to curb tumor growth. Reis also wants to explore ways to manipulate the system by which altered T cells enter the tumor.

“Perhaps we might one day fashion T cells into Trojan horses that can act as anti-cancer cells right inside the tumor microenvironment,” says Reis.

The study is published in the journal Science.