Probiotics have been shown to promote well-being in many and varied ways. Most of the probiotics ingested as dietary supplements and in dairy products, however, never reach their site of action in the small intestine. Scientists at Nanyang Technological University (NTU) in Singapore may have a solution to the dilemma. They’ve developed probiotics with a unique, edible coating that enables the beneficial bacteria to reach the intestine alive.

Probiotics are defined by the World Health Organization as live microorganisms which, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host. They help prevent infections of the urinary and digestive tracts, and maintain a healthy gut flora, which is linked to reducing the risk of obesity and to promoting overall well-being.

Many studies show that the bulk of probiotics delivered in commercial supplements and yogurts die within the first 30 minutes of exposure to the acidic environment of the stomach. Quantities which reach the small intestine alive are insufficient to benefit health.

In the NTU study, the probiotics, Lactobacillus casei bacteria, were spray-coated with alginate, a carbohydrate derived from brown algae. In experiments simulating the conditions in the human digestive tract, probiotics with the alginate coating survived the stomach’s acidic condition. The bacteria were released when they reached the small intestine, where the coating broke down. It reacted with phosphate ions, present in greater numbers than in the stomach.

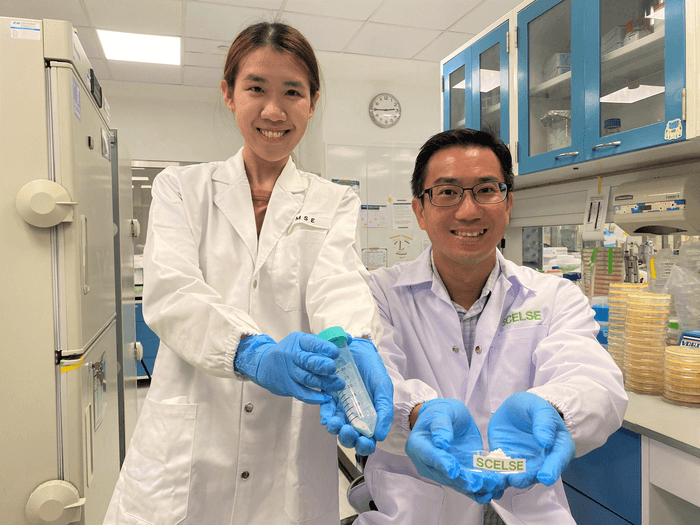

“Probiotics are delicate microorganisms and cannot survive the harsh environment of our stomach,” explains lead investigator, Associate Professor Joachim Loo of NTU’s School of Materials Science & Engineering. “To increase the efficacy of probiotics as a dietary supplement, we sought to ‘parcel-wrap’ and deliver them to specific sites of the intestine where they function best. Moisture-stable packaging makes for more effective probiotic delivery and extends the shelf-life of the supplements.”

Tan Li Ling is a PhD student at NTU’s School of Materials Science & Engineering who co-authored the study. “We selected alginate for the coating, as it is safe for human consumption, of natural origin, and relatively low-cost,” says Ling. “Alginate also exhibits acid-buffering properties, which can protect the probiotics against the harsh conditions caused by gastric acid.”

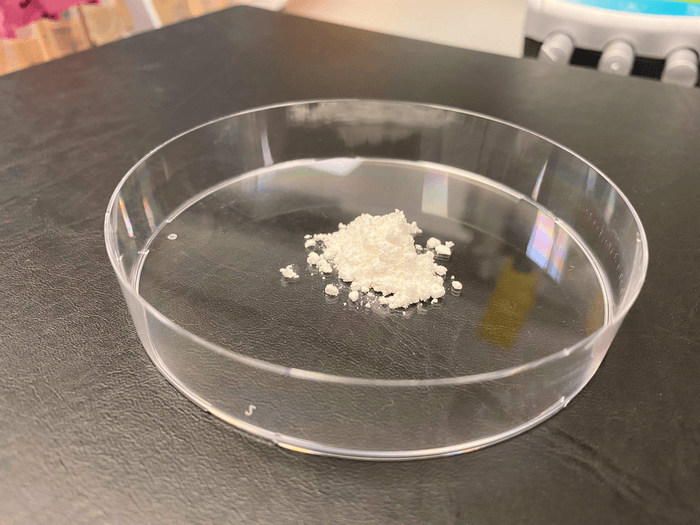

To make the coated probiotics, the bacteria are washed in a salt solution. Sugars are used with the alginate, to protect the live bacteria during manufacturing. The use of calcium ions extends the products’ shelf-lives. The compound is packed together in a predetermined concentration. The coating is applied using a spray-drying technique commonly used by the food and pharmaceutical industries. The coated probiotics can be produced affordably and in large quantities.

When refrigerated, the coated bacteria can survive for more than eight weeks, without degradation of the coating. Probiotic drinks have a shelf life of up to seven weeks when refrigerated, but after a few hours at room temperature the live bacteria start to die.

Besides potentially serving as a more effective way to deliver probiotics, the NTU scientists are exploring using their innovation to enrich food and drinks, such as beer and other canned beverages, and even animal feeds.

The findings are published in the journal Carbohydrate Polymers.