If you haven’t added mouthwash to your oral hygiene routine, here’s why you should start ASAP. Researchers from the Medical University of South Carolina found that microbes in your mouth regulate the interaction with immune cell activation of specific bone cells in charge of breaking down your jaw bone. However, early animal studies showed that using an antiseptic mouthwash protected against bone loss.

The alveolar bone, also known as the jawbone, is bone tissue that supports the teeth. The findings suggest the oral microbiome — species of bacteria, viruses, and fungi living in the mouth — is associated with the process of bone loss in the jawbone.

“Although we’re broadly suppressing oral microorganisms with the antiseptic rinse, it will be important to determine which specific microbes are really driving this naturally occurring alveolar bone loss,” Jessica D. Hathaway-Schrader, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar in the College of Dental Medicine and lead author of the study said in a statement. “The alveolar bone marrow is a unique environment, and this is the first step in understanding interactions between oral microbes and immune cells important for promoting bone health.”

Understanding the mechanisms behind weakening or loss of the jawbone may help researchers develop better treatments to prevent bone loss.

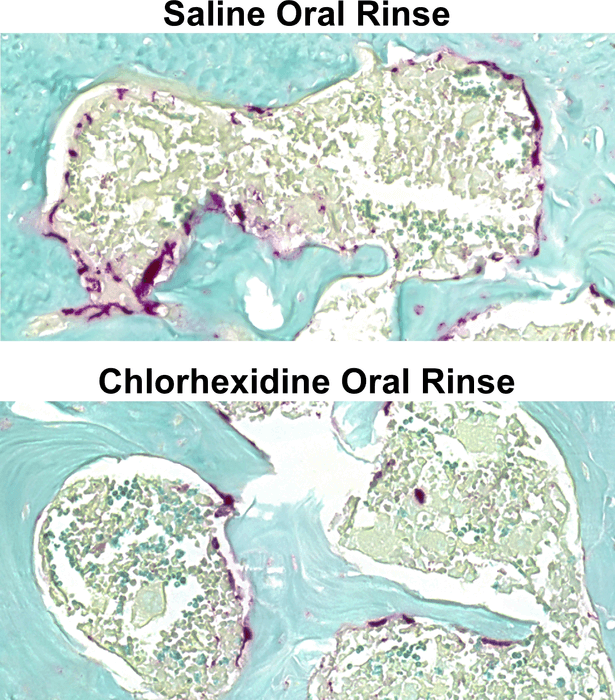

The current study focused solely on the oral microbiome because microbes in the mouth are near the alveolar bone. The team used two techniques to study the relationship between microbes and the alveolar bone. The first technique collected bone marrow from the lower jaw of mice where the researchers studied immune cells inside the alveolar bone. The second technique worked on a method to lower the number of microbes in the oral cavity of mice, which later resulted in the mouse version of a “mouthwash.” Mice received oral rinses of a sponge soaked with an antiseptic called chlorhexidine used to treat gingivitis.

The oral rinses with chlorhexidine were successful in reducing the number of microbes in the mouth without harming other areas, such as the gut microbiome. Decreasing oral microbial species also caused a decrease in the immune response in the alveolar bone marrow. Further research showed having microbes present caused dendritic cells to alert other immune cells of invaders to the mouth. The microbial presence also activated CD4+ helper T-cells to create an immune response.

But with a decreasing number of microbes in the mouth, there was a dampened immune response that stopped the activation of osteoclast cells — cells that break down bone. Suppressing osteoclasts shielded the jaw bone from further bone loss.

The study was published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation Insight.