“The gut is a fascinating interface between an animal and the world it lives in,” says John Rawls, Ph.D., director of the Duke Microbiome Center. That’s particularly true after examining the results of new research by Rawls and his colleagues, showcasing the extraordinary level of communication and regulation occurring in the digestive tract. According to their new study in mice at Duke University, the microbes that help break down food tell the gut how to do its job better.

“The gut receives information from both the diet and the microbes it harbors,” explains Rawls, professor of molecular genomics and microbiology, in a statement. It appears that the microbes influence which of the gut’s genes are being called into action. In turn, that interaction might lead to a remodeling of the epithelial cells lining the gut so that they match the diet.

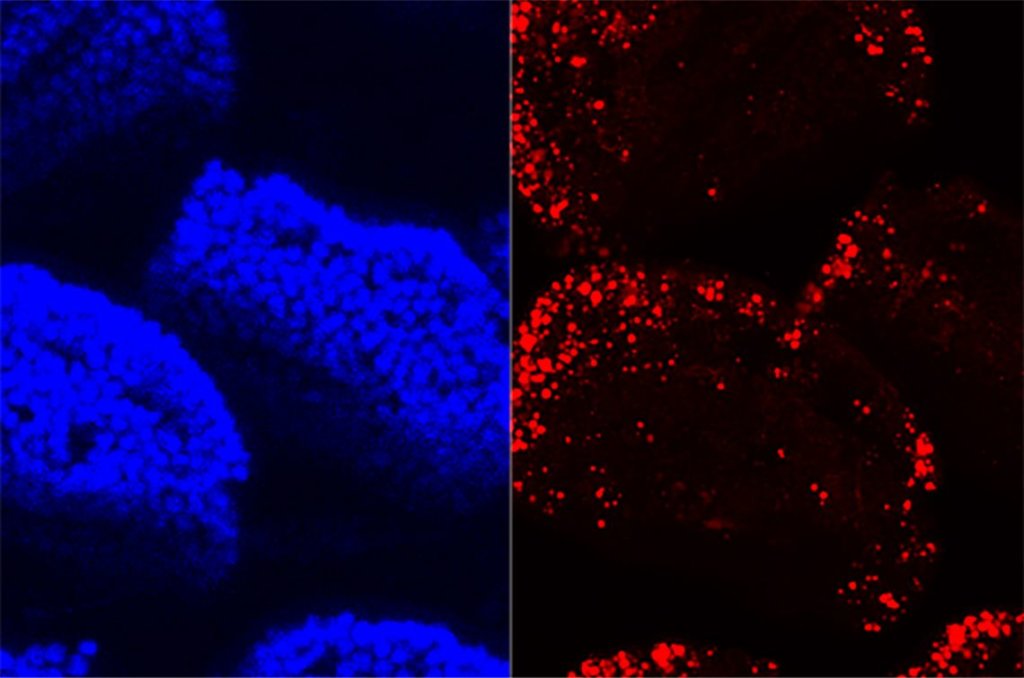

The scientists compared mice raised without gut microbes and those with a normal gut microbiome. Researchers focused on the crosstalk between DNA being copied to RNA and proteins that regulate the copying process in the small intestine, where most uptake of fat and other nutrients occurs.

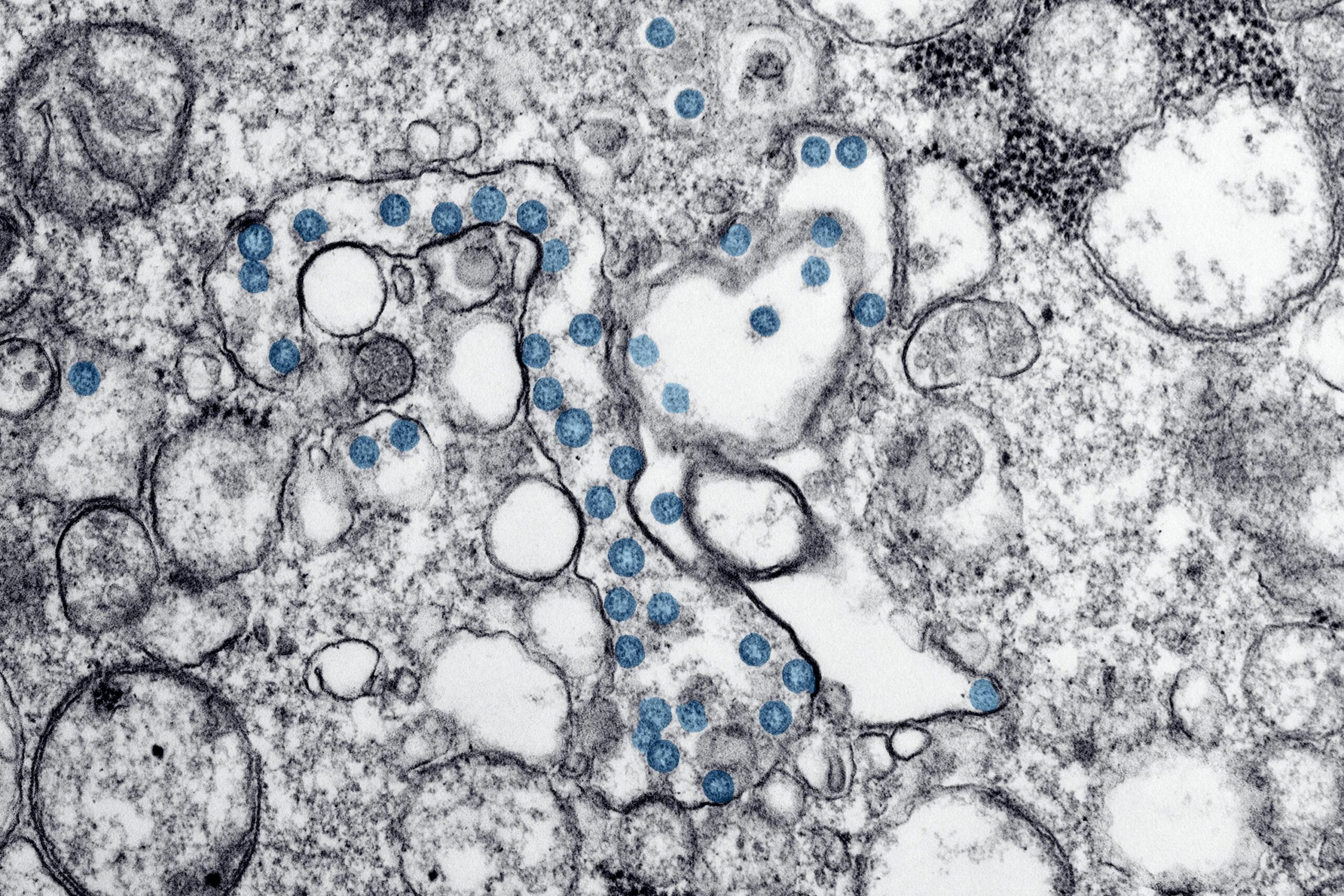

Both the germ-free and normal mice metabolized fatty acids in a high-fat diet, but the germ-free animals used a different set of genes. The microbes also help the gut absorb fats. “We were surprised to find that the gene playbook that the gut epithelium uses to respond to dietary fat is different, depending on whether or not microbes are there,” Rawls says.

“It’s a relatively consistent finding across multiple studies, from our lab and others, that microbes actually promote lipid absorption,” adds Colin Lickwar, Ph.D., senior research associate in Rawl’s lab. “That, at some level, also impacts systemic processes like weight gain.”

The germ-free mice had an increase in activity of the genes involved in fatty acid oxidation, with burning of fatty acids to provide fuel for the gut’s cells.

“Typically, we think about the gut just doing its job absorbing dietary nutrients across the epithelium, to share with the rest of the body, but the gut has to eat too,” Rawls says. “So, what we think is going on, in germ-free animals, is that the gut is consuming more of the fat than it would if the microbes were there.“

That may reflect differences in the composition of the gut’s epithelial cells.

Attention was focused on a transcription factor called HNF4-Alpha, known to regulate genes involved in lipid metabolism and genes that respond to microbes. “It’s certainly complicated, but we do appear to identify that HNF4-Alpha is important in simultaneously integrating multiple signals within the intestine,” Lickwar says.

“For every way that germ-free animals seem unusual, that teaches us something about the large impact of the microbiome on what we consider to be ‘normal’ animal biology,” Rawls adds.