The exact cause behind inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is unknown, but one group of researchers from Weill Cornell Medicine suggests it could be the work of toxin-producing yeast strains in the gut.

Their latest study finds that Candida albicans yeast strains can secrete a toxin called candidalysin that weakens the immune system, triggering uncontrolled intestinal inflammation.

“Such strains retained their ‘high-damaging’ properties when they were removed from the patient’s gut and triggered pro-inflammatory immunity when colonized in mice, replicating certain disease hallmarks,” says senior author Dr. Iliyan Iliev, an associate professor of immunology in medicine and a scientist in the Jill Roberts Institute for Research in Inflammatory Bowel Disease at Weill Cornell Medicine in a statement.

IBD affects about 3.1 million people living in the United States. The condition can impair a person’s quality of life, and while treatment options are available, they have limited effectiveness. One example is steroids, which are commonly prescribed to people with IBD to suppress intestinal inflammation.

In the current study, however, researchers found that giving steroids to mice did not help with inflammation when the C. albicans yeast strain was present.

“Our findings suggest that C. albicans strains do not cause spontaneous intestinal inflammation in a host with intact immunity,” Dr. Iliev explains. “But they do expand in the intestines when inflammation is present and can be a factor that influences response to therapy in our models and perhaps in patients.”

Unlike other research that focused on bacteria and viruses from the gut microbiome and their role in IBD, this study looks at fungi’s contribution to disease. Prior work from the team found that some fungi living in the gut help regulate the immune system in the intestines and the lungs. However, other types of fungi known as the mycobiota are linked to diseases such as IBD, although how they cause disease remains a mystery — until now.

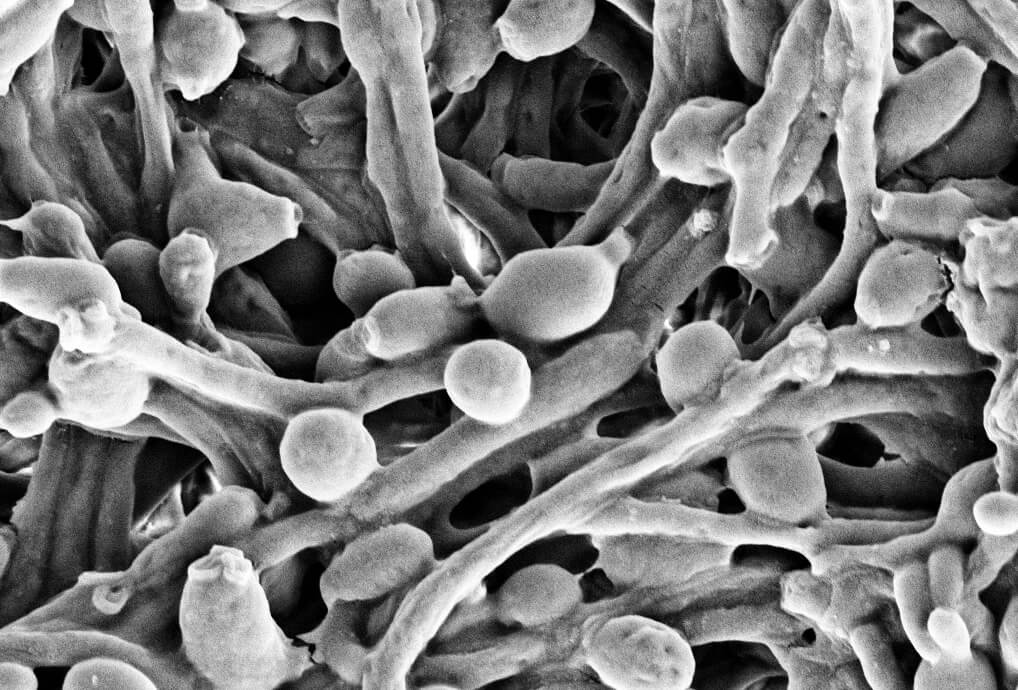

The Candida strains are present in every person’s intestines, but they were at higher levels among people with IBD. To understand how they cause disease, they studied the microbes in a person with ulcerative colitis. Severe disease resulted in the presence of “high-damaging” Candida strains that all produce a candidalysin toxin. The toxin injures immune cells called macrophages and provokes a cytokine storm.

A pro-inflammatory cytokine called IL-1β caused the high inflammation. When the team grew their own macrophages and exposed them to Candida strains, they found the toxicity depending on the severity of the disease.

“Our finding shows that a cell-damaging toxin candidalysin released by ‘high damaging’ C. Albicans strains during the yeast-hyphae morphogenesis triggers pathogenic immunological responses in the gut,” comments first author Dr. Xin Li, a postdoctoral fellow in the Iliev laboratory at the time of the study.

In mice, the “high-damaging” Candida strains caused an increase in other immune cells such as Th17 and neutrophils. All are involved in stimulating an inflammatory response.

“Neutrophils contribute to tissue damage and their accumulation is a hallmark of active IBD,” says Dr. Ellen Scherl, a gastroenterologist at New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center and a professor of IBD. “The indication that these processes might in part be driven by a fungal toxin released by yeast strains in specific patients could potentially inform personalized treatment approaches.”

Blocking IL-1β signaling helped prevent inflammation and signs of colitis in mice that have the Candida yeast strains in their gut. The findings suggest an IL-1β inhibitor could serve as a potential treatment avenue for IBD.

“We do not know whether specific strains are acquired by specific patients during the course of disease or whether they have been always there and become a problem during episodes of active disease,” says Dr. Iliev. “Nevertheless, our findings highlight a mechanism by which commensal fungal strains can turn against their host and overdrive inflammation.”

The study is published in Nature.