The first scientific evidence that microorganisms are part of the normal human system emerged in the mid-1880s, with Austrian pediatrician Theodor Escherich. The microbes were deemed dangerous. Things have changed. A new study from the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center describes the microorganism Candida albicans, a fungus, as friend rather than foe.

“This fungus could be invisible to our bodies if it wanted to be. It can mask many of the ways our immune system knows how to recognize it,” explains Dr. Sing Sing Way, infectious diseases expert at Cincinnati Children’s, in a statement. “Instead, our work shows that it purposely exposes itself to gain the benefit of our bodies recognizing it and not attacking it.

“This paper shows that commensal fungi need to be alive and actively making proteins that stimulate our immune cells to elicit that commensal benefit. They need to be metabolically and transcriptionally active,” Way adds.

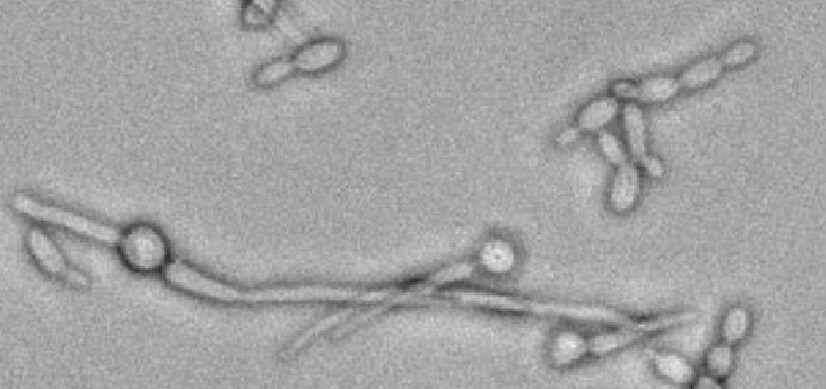

To determine how C. albicans becomes recognized as commensal, Tzu-Yu Shao, an Immunobiology graduate student, in collaboration with scientists at numerous academic institutions, conducted a series of experiments establishing C. albicans colonization in mice.

They learned that the gene UME6 is essential for allowing intestinal C. albicans to “prime” the immune system to prevent numerous, diverse infections. Initially, the team expected this priming effect to be caused by either extremely high or extremely low expression of this gene. Instead, the priming effect did not occur when colonization with C. albicans was at either extreme.

When the team engineered the fungus to oscillate between high and low levels of UME6 expression during colonization, it appeared to signal the body that C. albicans is beneficial. In rapid response, fungi help prevent infection by a variety of microbes—including C. albicans.

“We found that not only does the fungus have to be living, but it also must intentionally express specific cell wall components so that our bodies can detect them. They are deliberately doing that to help us and themselves,” Way says.

Eventually, it may be possible to manipulate this process to restore healthy levels of commensal fungi. First, Way’s team seeks to learn more about how this symbiotic relationship works.

The team also plans to explore how commensal C. albicans works in other tissues, including oral mucosa, lungs, skin, and the vagina.

The study is published in the open-access journal Cell Reports.