As with all cancers, narrowing down the cause is, for the most part, speculation. In the realm of breast cancer, researchers from the University of Virginia Cancer Center have encouraging evidence to help other researchers and oncologists to understand the nature of the disease.

Scientists say they’ve discovered that a disrupted gut microbiome alters mast cells, or immune cells in breast tissue, which ultimately helps cancer spread.

“We show gut commensal dysbiosis, an unhealthy and inflammatory gut microbiome, systemically changes the mammary tissues of mice that do not have cancer. The tissue changes enhance infiltration of mast cells that, in the presence of a tumor, facilitate breast tumor metastasis,” says researcher Melanie R. Rutkowski, PhD, of UVA Cancer Center and the University of Virginia School of Medicine.

This isn’t Rutkowski’s first go-round with breast cancer research, as she is the first to reveal such a connection. In this newer work she expands on her own findings by newly proposing that unhealthy gut bacteria influences the mast cell count and function when tumors are present.

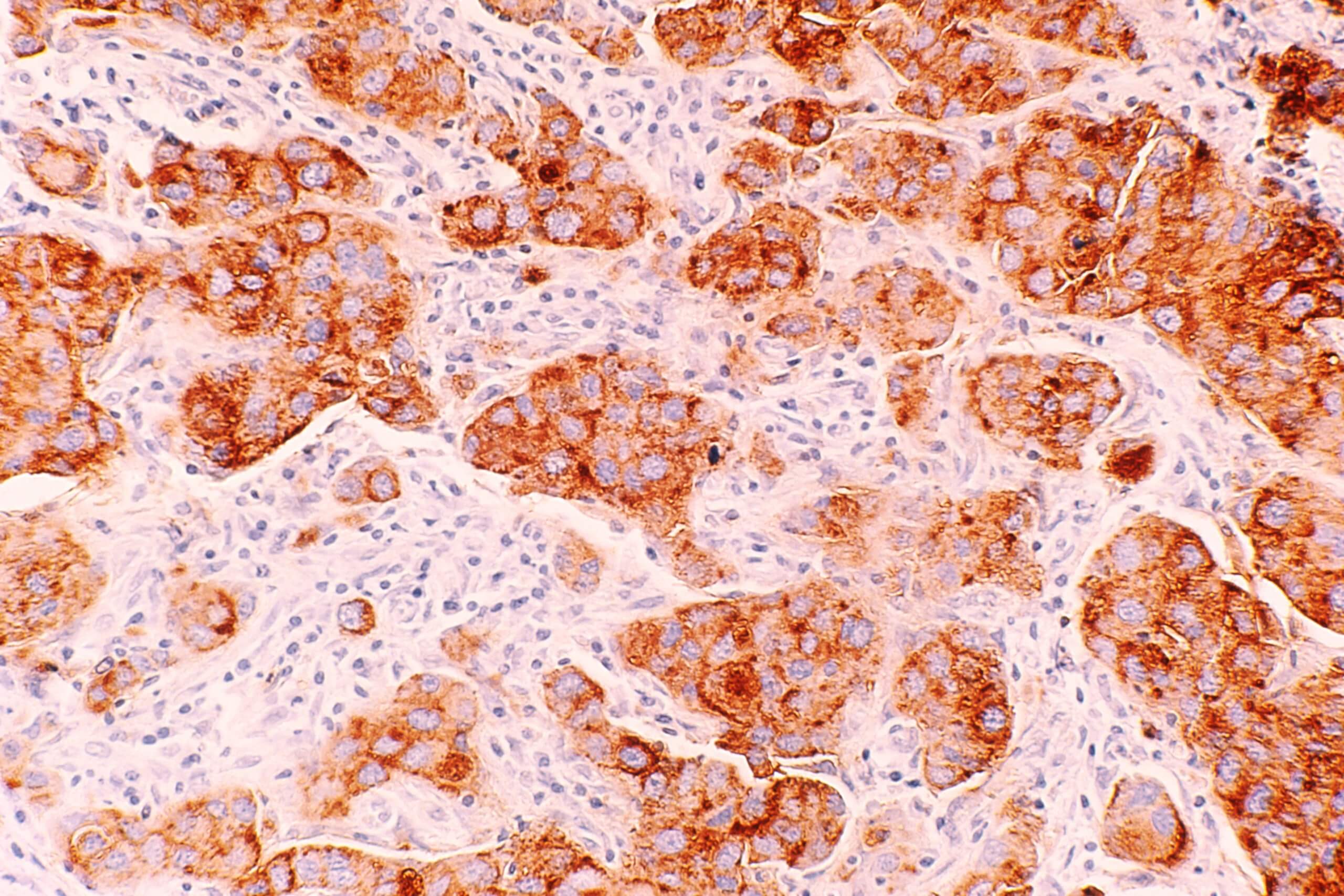

The team also examined tissue samples taken from human patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. During their experiments they noted that mast cell buildup occurred post-tumor growth in mice modeled with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Similarly to mice, the humans also accumulated mast cells and additionally showed increased collagen deposits.

Essentially, there was a consistent relationship between amount of collagen and mast cells, and subsequently breast cancer recurrence. In mice, they were able to stop the process leading to harmful growth by inhibiting it from even beginning.

“Mast cells have had a controversial role in breast cancer, with some studies identifying a positive correlation with outcome while others have identified negative associations,” explains Rutkowski, of UVA’s Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Cancer Biology. “Our investigation suggests that to better define the relationship between mast cells and risk for breast tumor metastasis, we should consider the mast cell functional attributes, tissue collagen density and mast cell location with respect to the tumor.”

She concludes that this research offers a promising strategy for stronger personalized oncology practices that lead to healthier patients and more effective care. Doctors may be able to use this relationship as a different target for halting breast cancer spread and recurrence in patients in remission. Rutkowski and team don’t plan to stop here, and agree that the objective is to improve breast cancer survival odds as much as they can.

This study is published in the journal Cancer Immunology Research.