Supplying clean, drinkable water to the world’s children can be a matter of life and death. Engineers, including those at Tufts, have devised simple, low-cost ways to purify drinking water in low-income countries using chlorine. They have found that using chlorine to treat drinking water in Dhaka, Bangladesh reduces diarrhea and antibiotic use, without disrupting the normal population of bacteria in the digestive tract of children.

More than 2,000 children die every day around the world because they lack clean drinking water, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. It had been a common concern, however, that adding chlorine to water could harm the beneficial bacteria in children’s developing gut microbiomes, which play an important role in maintaining the children’s health.

A team of scientists led by Tufts, the University of California at Berkeley, the International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research, Bangladesh, and Eawag in Switzerland collaborated in this life-saving research.

One year after children had been drinking chlorinated water, stool samples were collected. They had a similar diversity and abundance of bacteria as children who didn’t consume chlorinated water. Some slight differences were observed, but those were small and the overall make-up of their microbiomes was similar.

While chlorine inactivates microorganisms present in water during storage, transport, and delivery through the tap, this study suggests that it is not killing beneficial bacteria after the chlorinated water is consumed. By killing harmful bacteria in the water supply, chlorination allows the kids’ microbiomes to maintain good health.

The gut microbiome of infants is seeded at birth, then grows and stabilizes to its adult-like state by the time a child is about three years old. The progressive colonization by different bacteria in the microbiome may be important to several developmental milestones related to metabolism and weight maintenance, allergy development, disease susceptibility, and even mental health.

“No doubt further studies may be helpful for understanding all the long-term health effects of drinking chlorinated water,” says Maya Nadimpalli, assistant professor in civil and environmental engineering at Tufts, in a statement, “but this study makes it clear that the microbiome is protected after at least one year of exposure, so that the benefits of water chlorination—which can save hundreds of thousands of lives each year— outweighs diminishing concerns about its safety.”

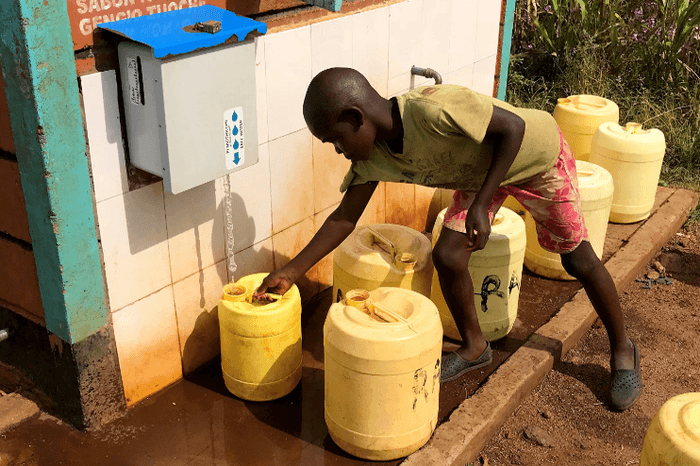

Amy Pickering, Blum Center Distinguished Chair in Global Poverty and Practice at the University of California, Berkeley, develops and field tests automated chlorination devices that are compatible with water infrastructure in Africa and Asia. “It’s very encouraging that such a widely used and low-cost water treatment method doesn’t harm children’s developing microbiomes,” she says.

Nadimpalli, whose research is conducted in collaboration with the Stuart B. Levy Center for Integrated Management of Antimicrobial Resistance at Tufts, notes that children in Bangladesh are frequently exposed to pathogens, and are treated with antibiotics at a rate five times higher than children in the U.S.

“The treatments themselves have a harmful effect on diversity in the gut microbiome, and you end up with worse health outcomes and potentially more antibiotic-resistant pathogens,” she says. “So chlorination can help reduce incidence of disease, limit use of antibiotics, and still keep microbiomes healthy.”