A recent study on fruit flies from Brown University is creating a buzz in the scientific community with a finding that could change how we think about aging. It turns out that a tiny, unassuming hormone produced in the fly’s gut plays a surprisingly powerful role in its aging process. The most provocative discovery? This hormone is part of the same family as the gut hormones that are targeted by some of the newest and most popular drugs for diabetes and obesity, like Ozempic and Wegovy. While this research was conducted on flies, the findings prompt a fascinating question: how might these increasingly common medications be affecting our own aging processes?

This discovery challenges some long-held beliefs about aging. For a long time, scientists have known that dietary restriction—or simply eating less—can extend the lifespan of many animals. It was largely believed this was a direct result of lower calorie intake. However, this new study, published in the journal PNAS, reveals a more complex picture. Researchers found that the lifespan benefit of eating less can be reduced simply by manipulating a specific gut hormone in the fly. This breakthrough highlights that the body’s response to food, not just the total calories, is a crucial part of the aging equation.

The Gut-Brain Connection to Longevity

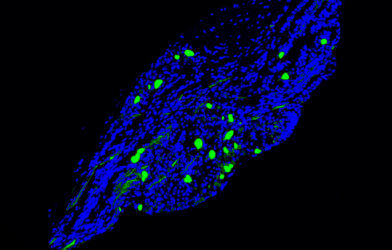

The central player in this story is a hormone called neuropeptide F, or NPF. In flies, NPF is produced in the gut and acts as a tiny messenger, carrying signals from the digestive system to the brain. The researchers discovered that when they lowered the amount of NPF in the flies’ guts, the flies lived longer. Conversely, when NPF levels were increased, their lifespans shortened. This led to an exciting conclusion: a communication pathway from the gut to the brain, mediated by this hormone, appears to be a major regulator of aging in flies.

To uncover this new aging pathway, the scientists needed to get creative. They developed a new way to directly measure the amount of NPF secreted into the flies’ hemolymph—the insect equivalent of blood. This novel approach allowed them to accurately track how diet and feeding affected NPF levels. The research team then performed a series of experiments using a large sample of female fruit flies and measured their lifespans under various conditions.

A Domino Effect: Gut, Brain, and Aging

The experiments painted a clear picture. The researchers found that NPF from the gut signals to the brain’s insulin-producing neurons, which in turn regulate the level of another hormone called juvenile hormone, or JH. In insects, JH is a key hormone that controls development and reproduction. The study found that by reducing NPF in the gut, the flies produced less insulin in their brain, which then led to a decrease in JH levels. The researchers confirmed that the decrease in JH levels was the ultimate factor that extended the flies’ lifespans. To prove this, they treated the flies with a synthetic version of JH, and the longevity benefits from the NPF manipulation were completely reversed.

The findings of this paper offer a powerful case for considering how our gut, brain, and other organs communicate to regulate our lifespan. This research marks a turning point where we can no longer view our bodies as a collection of separate parts, but rather as an interconnected system. The link between hormones like NPF and the aging process is a provocative new area of research that could revolutionize our understanding of how to live longer, healthier lives.

Paper Summary

Methodology

The researchers developed a novel method to directly measure the levels of a hormone called Neuropeptide F (NPF) in the hemolymph (blood) of adult female fruit flies. They used genetic tools to tag NPF with biotin, which allowed them to collect and quantify the hormone using a special test called an ELISA. The team used large sample sizes of fruit flies and measured their lifespans under different dietary conditions while genetically manipulating NPF levels in different gut cell types. They also knocked down the NPF receptor in specific brain neurons to determine the effect on lifespan and measured levels of other hormones and gene expression to establish a complete hormonal communication pathway.

Results

The study found that Neuropeptide F (NPF) is an incretin hormone secreted from gut cells in response to feeding. The suppression of NPF in the gut or its receptors in the brain’s insulin-producing neurons significantly extended the flies’ longevity. This longevity was shown to be dependent on a subsequent reduction in a hormone called Juvenile Hormone (JH). The researchers demonstrated a clear gut-brain-corpora allata axis, where gut NPF regulates insulin secretion from the brain, which in turn controls the production of JH. JH was identified as the ultimate endocrine factor regulating aging in this pathway, as treating the flies with a JH analog reversed the longevity benefits.

Limitations

The study was conducted on fruit flies, and while the hormonal pathways have similarities to those in humans, the findings do not directly translate to human aging. The study also noted differences in how the NPF pathway affects male and female flies, indicating that more research is needed to fully understand the sex-specific effects. The research focused on a specific gut-brain axis, and the authors acknowledge that there are multiple other pathways that can influence JH synthesis and aging.

Funding or Disclosures

The authors of the paper are Jiangtian Chen, Marcela Nouzová, Fernando G. Noriega, and Marc Tatar. The authors declared no competing interests. The article is a PNAS Direct Submission and is open access.

Paper Publication Info

The paper, titled “Gut-to-brain regulation of Drosophila aging through neuropeptide F, insulin, and juvenile hormone,” was authored by Jiangtian Chen, Marcela Nouzová, Fernando G. Noriega, and Marc Tatar. It was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy o