An international team of researchers have made an exciting new discovery of a stem cell mechanism in the gut. They found what regulates stem cells in intestinal crypts.

Austrian researchers examined the stem cells in the intestinal epithelium — a layer of cells that coats the insides of your small and large intestines that takes in nutrients and keeps anything unwelcome out of your system. The intestinal epithelium renews itself every four to seven days using stem cells.

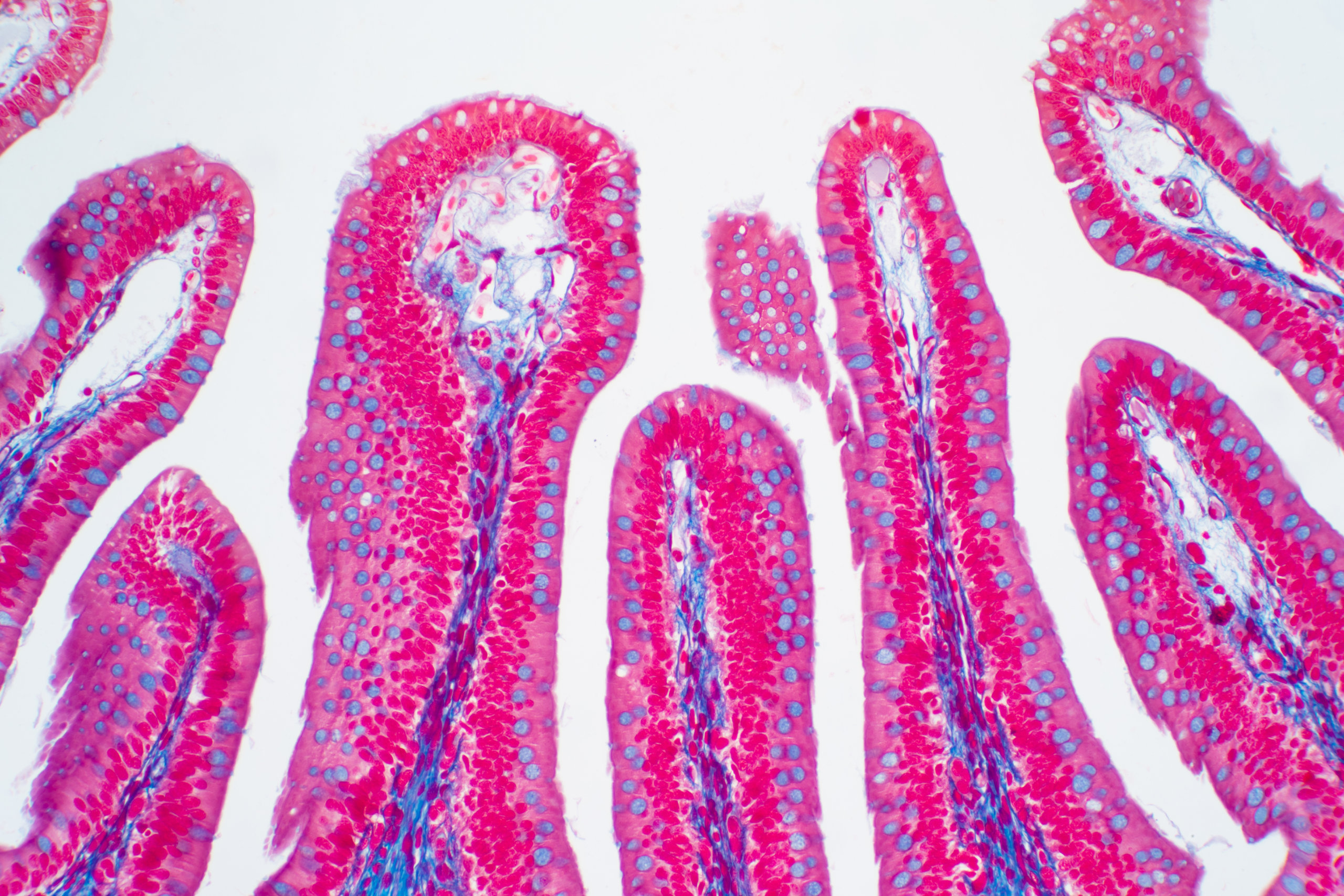

Researchers say the intestinal epithelium is all over the villi, which look like small tentacles covering the insides of the small and large intestines. Between the villi, there are tiny pockets in the tissue called intestinal crypts.

“At the bottom of the crypts, stem cells in the epithelium are constantly dividing. Some of the resulting cells remain as stem cells in the crypt and the others are pushed outwards towards the tip of the surrounding villi,” says Bernat Corominas-Murtra, an assistant professor at the University of Graz, in a media release. “There, in the end, they differentiate into functional cell types that allow intestinal function and which are discarded after a few days. This happens all the time inside your body and if this mechanism breaks down, you can get into serious medical trouble.”

Researchers say they were puzzled while examining these stem cells in the small and large intestines. They discovered that many of them never worked as stem cells. The cells were instead pushed out of the intestinal crypts to be discarded and didn’t contribute to the long-term renewal of the gut.

“We also saw that while classical markers predicted about the same number of stem cells in both the small and large intestines, there were about twice as many of them actually working as stem cells in the small intestine than in the large intestine,” notes Corominas-Murtra.

Scientists investigated what determined which cells act as stem cells and found a shocking new mechanism that regulates the stem cells in the crypts. “We found that whether these cells behave as a stem cell or not is all about their location! Cells in the epithelium are not just pushed outwards from the crypt by the cell divisions below them – like on a conveyor belt – but there is another kind of motion involved,” explains Corominas-Murtra.

The cells in the epithelium layer move around in random directions. Cells that were being pushed along the conveyor belt can end up back at the base of the crypt. These cells then act there again as stem cells to divide and renew the epithelium.

“These movements constitute a new environmental mechanism that determines which cells get to functionally act as stem cells. In the small intestine, the molecular signal regulating the movements is stronger than in the large intestine, so cells can move more frequently back into the crypt. This explains why there are more actually working stem cells in the small intestine than in the large ones. This could have major implications for our understanding of what a stem cell actually is and how to use them in medical applications,” says Edouard Hannezo, professor at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria.

Researchers ended up creating an advanced mathematical model of the intestinal epithelium layer. It included the motion of the cells both away from and back towards the crypt. The model was able to predict the number of actually working stem cells in the small and large intestines.

The study is published in the journal Nature.