Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have revealed two key transition points in the development of pancreatic cancer. These breakthroughs in understanding of these tumors are creating paths to more, and more effective therapies in this notoriously aggressive, difficult to treat disease, with a dismal survival rate.

If you take only one thing from reading this article, let it be this: hearing the “C” word does not have to freeze you in fear. I’ll say that again: Hearing the “C” word does not have to freeze you in fear. I’m talking about the word cancer. Phenomenal strides have been made in how, and how early in the course of the disease cancers are diagnosed, in the numbers and effectiveness of treatments, in the survival rates, in longevity with disease, and in quality of life in the presence of disease. The 5-year survival rate in female breast cancer is at an all-time high of greater than 90 percent. In 1980 it was about 76 percent.

Now, having offered reassurance that survival with cancers is greater than ever before, I’ll give you an exception – pancreatic cancer. The 5-year survival rate is about 11 percent. In 1980 it was about 2 percent. Slightly better now, but still dismal. There aren’t many treatment options.

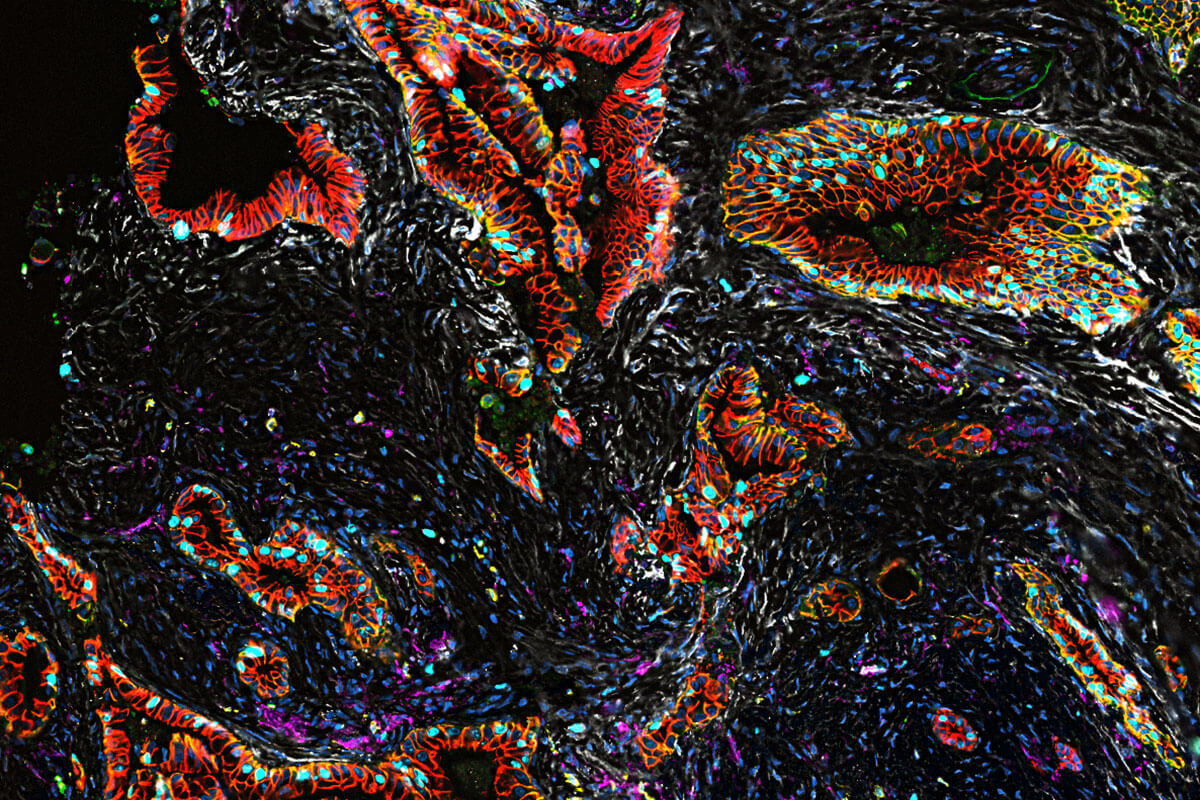

A detailed analysis of the pathophysiology of pancreatic cancer in 83 pancreatic tumors from 31 patients identified two key points in the development of the disease. The first is the shift from normal cells to precancerous cells, and the second key point is the change from precancerous to cancerous cells. The study also provides insights into treatment resistance and how immunotherapy could be used for treatment.

“Pancreatic cancer is so difficult to treat, and to develop better treatments we need to understand how normal, healthy cells in the pancreas transition to becoming cancerous,” says Li Ding, PhD, a professor of medicine and genetics who led the study, in a statement. “This marks the first time these transitions have been mapped out in such detail in pancreatic tumors. Our findings are jumping-off points for the future development of new treatment strategies for this deadly cancer.”

Over time, most pancreatic tumors develop resistance to chemotherapy, and the new study reveals what Ding calls a chemo-resistance signature that characterizes how the tumors change and adapt to survive — even in the face of chemotherapy.

The researchers found triple the usual number of inflammatory cells which surround tumors. Called inflammatory cancer-associated fibroblasts, these cells are strongly associated with resistance to chemotherapy.

“These findings suggest that targeting the inflammatory fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment may be key to overcoming chemo-resistance in these treated tumors,” Ding said.

The team is working in animal models to determine which are most amenable to investigation prior to human clinical trials. Their research paper is published in Nature Genetics.