The microorganisms living in our gut are a vital part of our health. Earlier research suggests they affect the rate at which the lining of certain organs regenerates, however, the mechanism by which these gut microbes do so has remained largely unknown – until now. Bacteria in the gut are found to secrete their metabolites into tiny vesicles that flow through the bloodstream, according to the study. This finding gives insight into the critical process by which gut microbes stimulate organs in the body.

Mounds of research have proven the significance of a healthy gut microbiome in the body, which has prompted researchers to study the methods behind their important functions. One such function is the production of metabolites via digestion. These metabolites aid cells of the immune system and stimulate the renewal of organ linings such as the liver, kidneys, and brain.

The metabolites can be directly absorbed in the intestines, however, other organs have specialized linings that serve as extra protection, such as the blood-brain barrier. Since the brain still gleans the effects of these bacterial secretions, researchers investigated the mechanism that allows them to cross this barrier.

Vesicle Transportation

Researchers from Goethe University Neuroscience Center, FAU (University of Erlangen-Nuremberg), and the University of California collaborated to determine the transport method that enables these metabolites to impact so many areas of the body. This was accomplished by infecting mice with E. coli in the gut. The E. coli generated a particular sort of gene “editor” called Cre that was packed into microscopic vesicles.

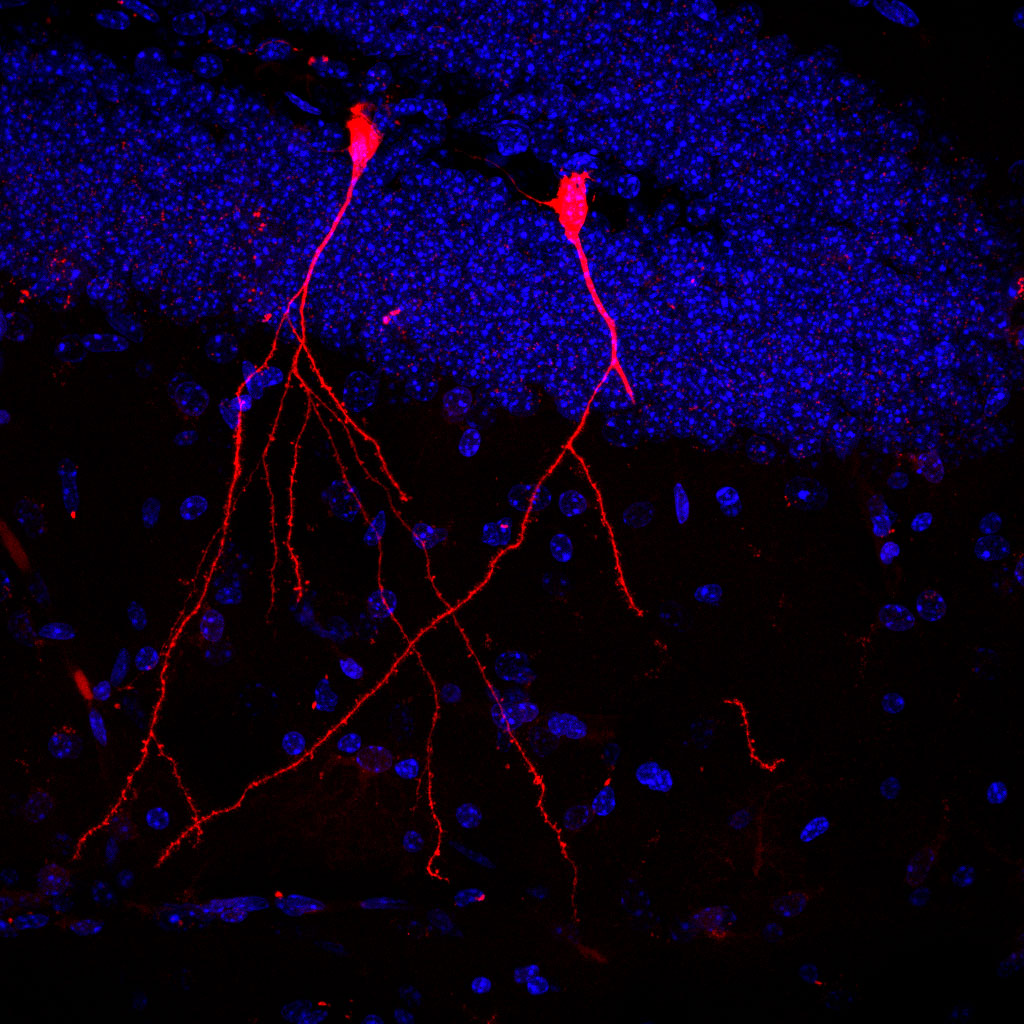

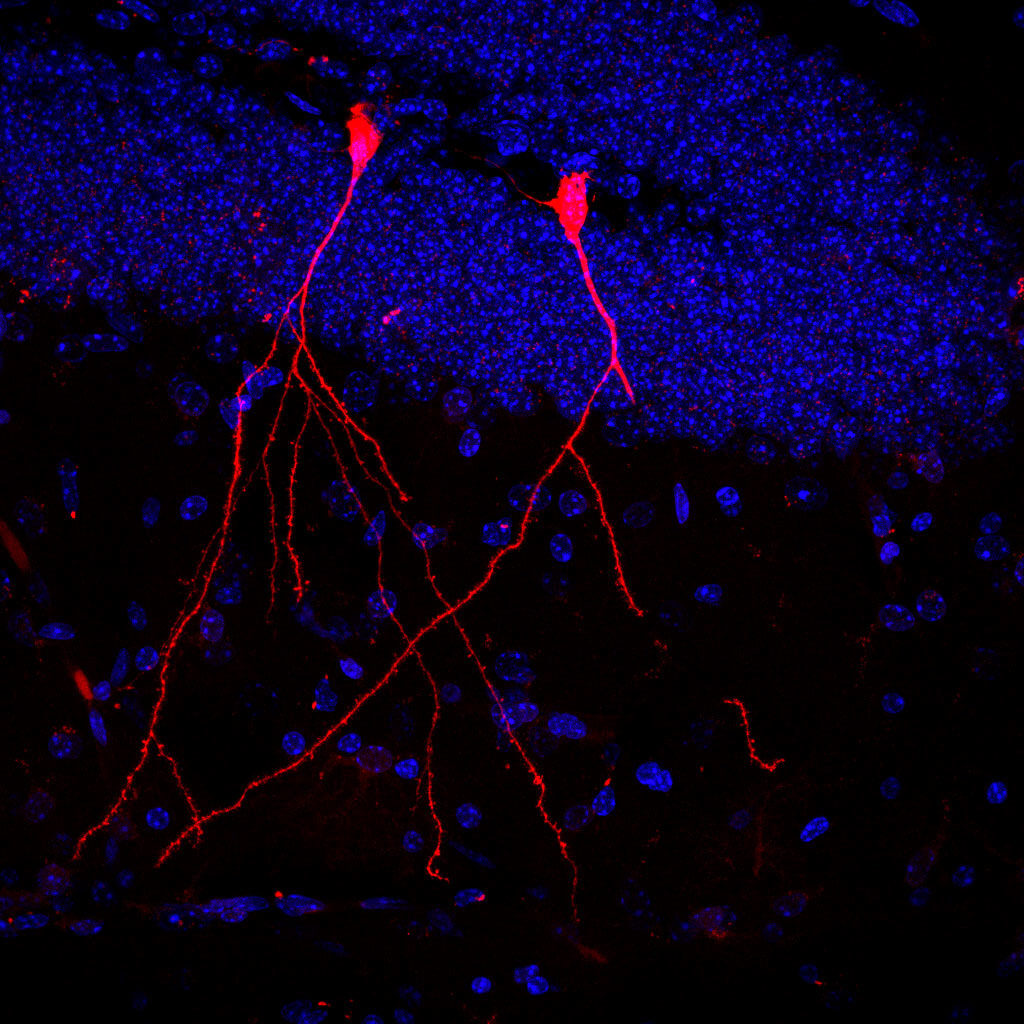

The cells of each mouse carried a gene encoding a protein that glows red in the presence of the Cre gene “editor”. Results revealed that the microscopic vesicles were taken up by gut, heart, liver, immune, and kidney cells. Thus, functional Cre housed inside the vesicles was able to penetrate the cells, resulting in the production of red luminescence. Furthermore, parts of the brain lit up bright red indicating the vesicles successfully crossed the blood-brain barrier.

“Particularly impressive is the fact that the bacteria’s vesicles can also overcome the blood-brain barrier and in this way enter the brain – which is otherwise more or less hermetically sealed. And that the bioactive bacterial substances were absorbed by stem cells in the intestinal mucosa shows us that intestinal bacteria can possibly even permanently change its properties,” says lead researcher, Dr. Stefan Momma, in a statement.

“The further study of these communication pathways from the bacterial kingdom to individual mammalian cells will not only improve our understanding of conditions such as autoimmune diseases or cancer, in which the microbiome quite obviously plays a significant role. Such vesicles are also extremely interesting as a new method to deliver drugs or develop vaccines, or as biomarkers that point to a pathological change in the microbiome,” Momma adds.

This study is published in the Journal of Extracellular Vesicles.