What if the food you put on your table, or the struggle to consistently put it there, was quietly rewriting the script for your brain health? It sounds like a stretch, but new research reveals a surprising and potent link between limited access to food, the unseen world of bacteria in your gut, and your risk of memory and thinking problems. This isn’t just about what you eat, but whether you have enough to eat, and how that fundamental reality could be influencing the very core of your cognitive abilities.

Scientists have long recognized the “gut-brain axis,” a two-way street of communication between your digestive system and your brain. We know that the trillions of microbes living in your gut—your gut microbiome—play a role in everything from your mood to your mental sharpness. But this latest study goes a crucial step further, demonstrating how a pervasive social issue like food insecurity, meaning uncertain access to enough food for an active, healthy life, can dramatically alter this gut-brain connection, potentially speeding up cognitive decline. It’s a powerful reminder that everyday stressors, especially those tied to basic needs, have a profound biological impact that reaches into the very depths of our minds.

Unraveling the Gut-Brain Link

To get to the bottom of this complex relationship, researchers conducted what’s known as an epidemiologic study. This type of research carefully examines health patterns in large groups of people to identify potential causes and risk factors for disease. For this study, the team focused on 360 adults from the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin (SHOW), a long-running statewide health survey. As part of SHOW, a special effort called the Wisconsin Microbiome Study (WMS) collected stool samples, giving scientists a rich collection of information about participants’ gut bacteria.

The researchers specifically looked at participants who had detailed information about their food security status, their risk of cognitive impairment (RCI), and genetic data from their gut microbes. Food insecurity was determined by simple questions: had they used emergency food services, worried about having enough food, or received Food Stamps in the past year? A “yes” to any of these meant they were considered food insecure. For assessing cognitive health, participants took an adapted “mini-cog” test. This isn’t a brain scan, but a practical way to check memory and thinking skills. Participants would remember three words and then draw a clock. Their ability to recall the words later provided a score indicating their likelihood of cognitive impairment—a higher score meant a greater risk.

It was important for the study to consider other factors that could affect both gut health and thinking skills. So, the researchers adjusted for things like age, body weight (BMI), gender, race, whether someone had a pet, their smoking habits, and even if they had recently taken antibiotics. This careful approach helps ensure that the findings truly point to the connection between food insecurity, gut bacteria, and cognitive health, rather than other influences.

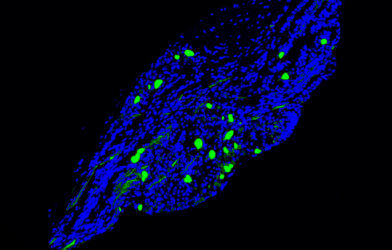

A significant innovation in this study involved looking at groups of microbes, not just individual types. Using a sophisticated computer method called Microbiome Co-occurrence Analysis (MiCA), the scientists identified “microbial cliques”—small, interconnected communities of bacteria that tend to live and work together. This allowed them to see how these bacterial teams, rather than just single species, were linked to cognitive health and how a person’s food security status might change those links.

The study’s participants included 292 individuals who were food-secure and 68 who had experienced food insecurity. Those who were food-insecure tended to be younger, had a higher average BMI, were less likely to be non-Hispanic White, and often had lower mini-cog scores, suggesting a higher risk of cognitive impairment. They were also more likely to be living below 200% of the poverty level. These differences underline the real-world disparities often connected to food access.

Surprising Links: How Food Access Alters Gut-Brain Signals

The study’s findings are quite striking. Not only did the research confirm that food insecurity itself was tied to an increased risk of cognitive impairment, but it also pinpointed two specific microbial cliques whose relationship with cognitive health was dramatically altered by whether a person had enough food.

For individuals facing food insecurity, the presence of a specific bacterial clique containing Eisenbergiella or Eubacterium showed a strong connection to a higher risk of cognitive impairment. The impact of this group of bacteria was much more pronounced in those struggling with food access compared to those who were food-secure. This outcome indicates that for people who are uncertain about where their next meal is coming from, these particular gut residents might be pushing them towards cognitive decline.

On the flip side, for individuals who were food-secure, a different bacterial clique—one including Ruminococcus torques, Bacteroides, and/or Eubacterium—had a stronger link to cognitive impairment. While this clique also showed an association with increased RCI in the food-insecure group, that connection was weaker than in their food-secure counterparts.

These contrasting results are a crucial discovery. They show that the same groups of gut bacteria can have different effects on cognitive health depending on a person’s food security status. As Shoshannah Eggers, Assistant Professor of Epidemiology at the University of Iowa College of Public Health and the study’s lead author, stated, “Food insecurity is consistently linked to adverse health outcomes such as poorer overall health and adverse neurological health outcomes. Understanding how gut health and social conditions interact gives us a fuller picture of what puts people at risk for cognitive decline.”

Why This Matters: Understanding the “How”

How can something like limited access to groceries impact the tiny organisms in your gut, and then, your brain? The researchers offer several compelling explanations.

One major player is stress. Living with food insecurity is a chronic, relentless stressor. Long-term stress can activate the body’s “fight or flight” response, a system that, when overactive, can harm memory and decision-making skills. The gut microbiome is thought to play a role in mediating this stress response.

Beyond stress, shifts in diet often accompany food insecurity. When access to nutritious food is limited, people may resort to eating more calorie-dense, but nutrient-poor, options. Such diets can reduce the diversity of beneficial microbes in the gut and create an imbalance between helpful and harmful bacteria. These changes in gut bacteria can influence how the gut processes food, potentially leading to less production of brain-supportive compounds.

For example, a healthy gut microbiome produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which are important for maintaining a strong gut barrier and for influencing brain function. When SCFA production drops due to an unhealthy gut, the gut lining can become more “leaky,” allowing bacterial byproducts to slip into the bloodstream. These harmful compounds can then reach the brain, triggering inflammation that could contribute to cognitive decline.

The specific bacteria found in the “problematic” cliques also offer clues. Many of these bacteria engage in “cross-feeding,” meaning they either break down complex molecules for other bacteria to use, or they rely on what other bacteria produce. For instance, Ruminococcus torques is known to break down a protective layer in the gut, providing simple sugars for other bacteria. The fact that these interacting groups of bacteria are specifically tied to cognitive risk, depending on food security, highlights the intricate nature of the gut-brain connection. Previous studies have indeed linked some of these bacteria to various aspects of neurodegenerative diseases and cognitive function, underscoring their potential role.

A New Path for Public Health

The findings of this study have significant implications. They suggest that simply ensuring people have access to food might not be the full solution; the consistency and quality of that access could be vital for maintaining brain health, particularly through its effects on the gut microbiome. As Vishal Midya, Assistant Professor of Environmental Medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and senior author of the study, summarized, “These findings suggest that food insecurity is not just a socioeconomic issue—it may be a biological one too, influencing brain health via changes to the gut microbiome.”

This research opens the door for more tailored public health strategies. Understanding how food security status changes the link between specific bacterial communities and cognitive risk means that future interventions—whether through diet, probiotics, or other microbial treatments—may need to be customized to an individual’s specific circumstances regarding food access to be truly effective. The path to a healthier brain, it seems, might just start with a full pantry.

Paper Summary

Methodology

This epidemiologic study included 360 adults from the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin (SHOW) and the Wisconsin Microbiome Study (WMS). Food insecurity was assessed via participant surveys. Risk of cognitive impairment (RCI) was measured using an adapted “mini-cog” test. Gut microbiome composition was analyzed from stool samples using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Microbiome Co-occurrence Analysis (MiCA) identified microbial “cliques,” and analyses were stratified by food insecurity status, adjusting for various confounders.

Results

The study found that food insecurity was independently associated with both poorer gut health and increased risk of cognitive impairment (RCI). Two specific microbial cliques showed associations with RCI that were modified by food security status. For food-insecure individuals, a clique with Eisenbergiella and/or Eubacterium was strongly linked to increased RCI. For food-secure individuals, a clique including Ruminococcus torques, Bacteroides, and/or Eubacterium showed a stronger association with increased RCI.

Limitations

Key limitations include the relatively small sample size (360 participants) and the study’s cross-sectional design, which prevents establishing cause-and-effect relationships. The findings’ generalizability may be limited as all participants were from Wisconsin. Potential for RCI misclassification and unmeasured confounding factors also exist.

Funding and Disclosures

The Survey of the Health of Wisconsin (SHOW) program, from which data was utilized, was primarily supported by the Wisconsin Partnership Program and the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation, both of the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The authors declared no competing interests.

Publication Information

The study, titled “Food insecurity modifies the association between the gut microbiome and the risk of cognitive impairment in adults,” was published in npj Aging in 2025. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-025-00241-0