Our bodies are exposed to millions of microorganisms each day, some good and some bad. Fortunately, our immune system is the sheriff of the body, ensuring that everything coming through is up to no suspicious activity. One reason the immune system is efficient most of the time is because of its ability to recognize between the self and non-self. New research from Harvard Medical School has uncovered how the immune system can distinguish between friend and foe.

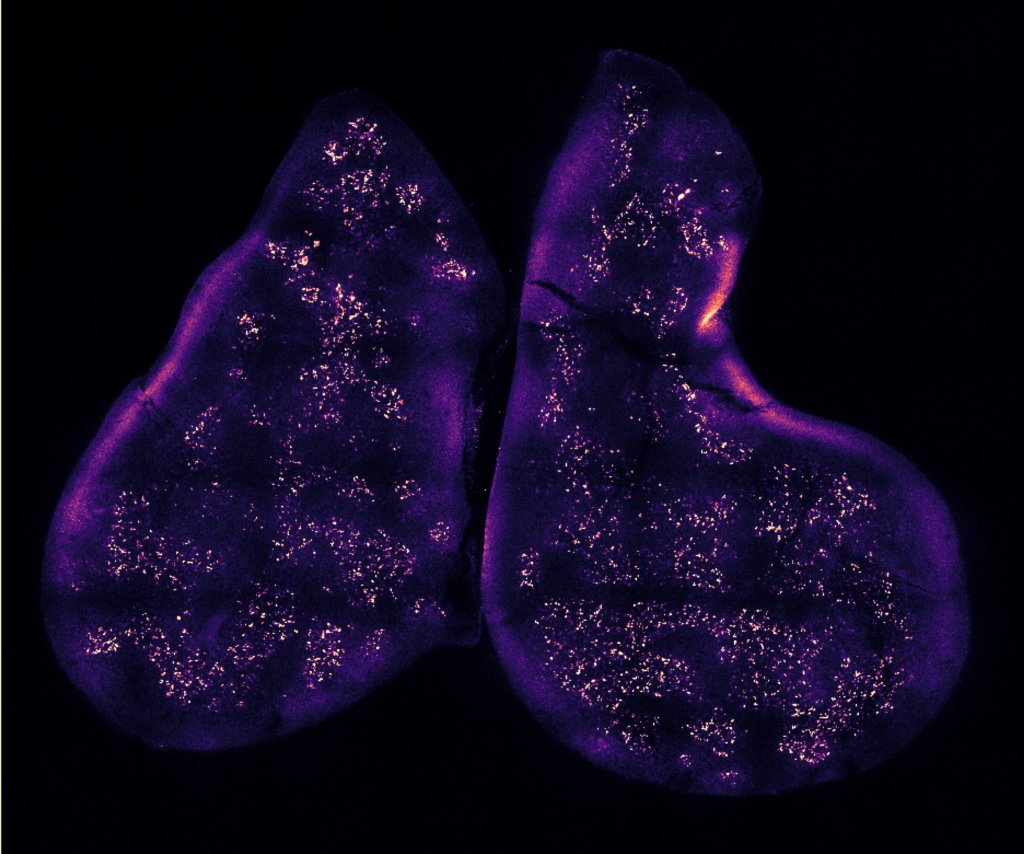

The immune system’s ability to differentiate a strange pathogen from the cells and tissue of the body is because of an immune cell called T-cells. Using mice, the researchers studied the thymus gland — the organ where T cells are born and trained —and found that new immune cells are exposed to proteins from thymus cells that mimic multiple tissues in the body. By showing the naive T cells a preview of what to encounter in the body, they will be better able to discern what’s part of the body and what’s not.

“Think of it as having your body recreated in the thymus,” says Diane Mathis, professor of immunology at Harvard Medical School and senior study author, in a statement. “For me, it was a revelation to be able to see with my own eyes muscle-like cells in the thymus or several very different types of intestinal cells.”

Adds co-author Daniel Michelson, a doctoral student at Harvard Medical School: “Our immune system is super powerful. It can kill any cell in our body, it can control any pathogen we encounter, but with that power comes great responsibility. If that power is left unchecked, it can be lethal. In some autoimmune diseases, it is lethal.”

In the study, the researchers found evidence that these teacher cells in the thymus gland use proteins that drive gene expression in specific tissues to mimic the identities of the skin, lung, liver, or intestine. These proteins are shown to immature T cells to teach self-tolerance, preventing them from laying a hand on these essential body parts.

This school-like process led by the immune system also serves another purpose. It’s also used to weed out T cells that are too destructive and mistakenly attack the protein. These T cells are weeded out by getting a command to self-destruct or transferred to another role that does not involve killing.

“The thymus says: This cell is autoreactive, we don’t want it in our repertoire, let’s get rid of it,” says Michelson.

The findings may help explain why some people develop autoimmune disorders. One likely reason could be the type of tissue the teacher cells are showing to emerging T cells. “We think it’s an exciting discovery that may open up a whole new vision of how certain types of autoimmune diseases arise and, more broadly, of the origins of autoimmunity,” says Mathis. The next steps will involve diving into the molecular mechanisms that are driving T cell education, the relationship between tissues shown to T cells and their function/dysfunction, as well as how the mechanism works in the human thymus.

The study is published in the journal Cell.