Hidden chatter between the gut and immune system are no longer a secret, thanks to researchers from La Jolla Institute for Immunology. A new study reveals how barrier cells that line the intestines send messages to the patrolling T cells that reside there.

These cells communicate through the HVEM protein. This protein prompts T cells to survive longer and stop potential infections.

“The research shows how barrier cells in the intestine, structural elements of the tissue, and resident immune cells communicate to provide host defense,” says study senior author Dr. Mitchell Kronenberg, LJI professor and chief scientific officer, in a media release.

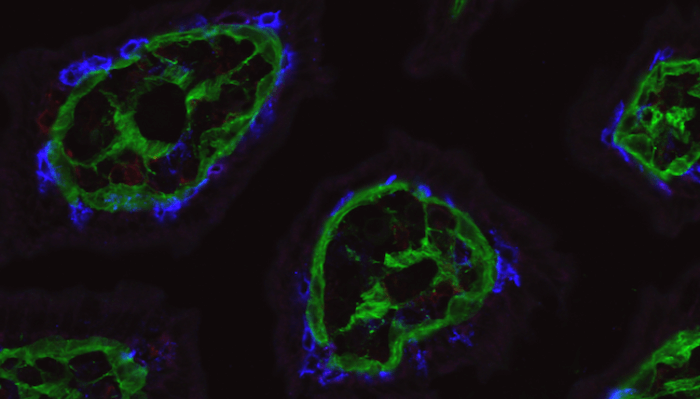

Researchers say barrier cells, or “epithelial” cells, form a one-cell thick layer that lines the gut. To put in layman terms: picture the epithelial cells lining up outside a busy bar. These cells squish together and jostle each other. In the meantime, T cell security guards move around the line, looking for signs of trouble.

“These T cells move around the epithelial cells as if they are truly patrolling,” notes Kronenberg.

The study found that critical signals in the gut are sent through the basement membrane, a thin layer of proteins beneath the epithelium. These epithelial cells receive signals through HVEM proteins on their surface that stimulate synthesis of basement membrane proteins. Researchers established that without HVEM, epithelial cells are unable to do their job. That’s because they produce less collagen and other structural components needed to maintain a healthy basement membrane.

Researchers say T cells detect the basement membrane through adhesion molecules they express on their surface. These are called integrins. As T cell integrins and basement membrane proteins interact, it promotes messages that allow the T cells to survive and patrol in the epithelium. T cells could not survive as well or go on patrol without a sufficient basement membrane.

To test this, researchers removed HVEM expression in the gut epithelial cells in a mouse model. This caused an intense blow to gut health. Researchers say patrolling T cells could not survive as well and didn’t move as much, making them poor security guards.

When T cells were opposed with Salmonella typhimurium, an invasive bacteria that causes gastroenteritis, these cells allowed the infection to take over the intestines and spread to the liver and spleen. Researchers say their results found that HVEM from epithelial cells laid the groundwork for T cells to guard the gut, interacting with the T cells indirectly through the basement membrane.

For the future, researchers are interested in exploring the role of HVEM in maintaining a healthy population of gut microbes. Researchers say there are signs that a lack of HVEM can sway the composition of the gut microbiome even in the absence of pathogenic bacteria.

The study is published in the journal Science Immunology.