Antibiotics have a bad reputation for eliminating good bacteria from the gut and promoting antibiotic-resistant strains. To circumvent this issue, scientists from Rockefeller University created narrow-spectrum antibiotics that limit damage to the gut by targeting only a few species of bacteria.

Their latest study shows that narrow-spectrum antibiotics are effective in selectively eliminating the harmful strain Clostridium difficile (C. diff) while sparing nearby and harmless bacteria.

“I want people, scientists, and doctors to think differently about antibiotics,” says Elizabeth Campbell, a research associate professor at Rockefeller in a statement. “Since our microbiome is crucial to health, narrow-spectrum approaches have an important part to play in how we treat bacterial infections in the future.”

C. diff is a toxic-producing bacteria that is the root of multiple infections including those involving severe diarrhea and inflammation of the colon. The bacterium infects about half a million people in the United States, especially in hospitals. One in 11 people over 65 infected with C. diff die within a month. In retaliation, doctors give broad-spectrum antibiotics but in 2011 an alternative narrow-spectrum antibiotic known as fidaxomicin was approved to treat C. diff infections.

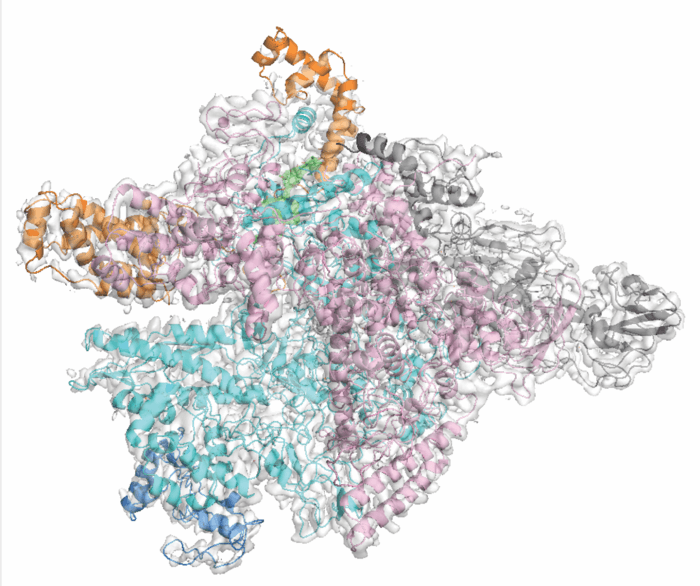

Fidaxomicin, like other antibiotics, targets an enzyme called RNA polymerase, which the bacterium uses to convert its DNA into RNA. The researchers sought to understand why fidaxomicin selectively stops RNA polymerase from transcribing the bacteria’s genetic information without harming other bacteria. Using cryo-electron microscopy to look at the 3D shape of molecules, the team could observe the drug molecules in action when exposed to large amounts of C. diff.

Fidaxomicin works by jamming two subunits of RNA polymerase and prevents it from grabbing genetic material to start transcription. The team also found one amino acid on the RNA polymerase binds to fidaxomicin, but they do not find this amino acid in other gut microbes not affected by fidaxomicin. When researchers exposed fidaxomicin to a genetically altered version of C. diff without the amino acid, it was left alone. On the flip side, bacteria that had the amino acid inserted were targeted by fidaxomicin.

The findings show this one out of 4,000 amino acids is the C. diff weakness, and the main reason behind fidaxomicin’s selective targeting of the bacterium. The team suggests understanding how to selectively neutralize dangerous bacteria while sparing other gut microbes could pave the way to creating safer and more effective antibiotics.

The study is published in the journal Nature.