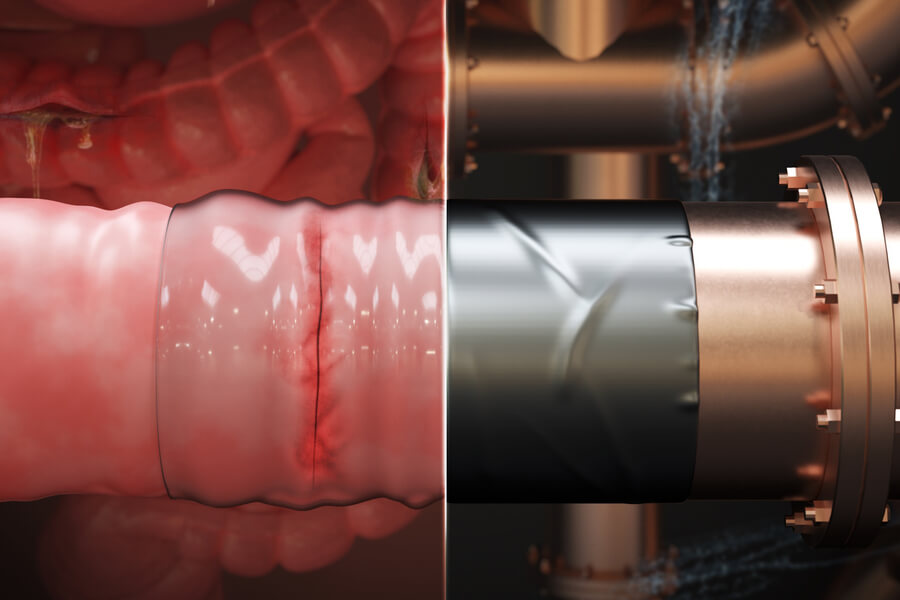

Scientists at MIT have created a super-strong “duct tape” of sorts for internal organs that could serve as an alternative to stitches. This surgical bandage could be quickly applied to repair gut leaks and tears.

Incredibly, this potentially game-changing innovation was inspired by the the humble spider. Engineers noticed how it exudes “glue” to catch prey in the rain. The secretion absorbed water, helping secure the next meal.

The sticky tape works in a similar way. It could replace sutures — stitches that hold a wound or cut together. They don’t always work well, and can cause infections and pain. It could also be used to attach medical devices to organs such as the heart.

“We think this surgical tape is a good base technology to be made into an actual, off-the-shelf product,” says lead author Dr Hyunwoo Yuk in a statement. “Surgeons could use it as they use duct tape in the nonsurgical world. It doesn’t need any preparation or prior step. Just take it out, open, and use.”

What is the internal ‘duct tape’ made from?

The material is strong, flexible and biocompatible. Like duct tape, the patch is sticky on one side and smooth on the other.

A special adhesive called polyacrylic acid, an absorbent material found in diapers, is targeted to seal defects in the gastrointestinal tract. It starts out dry and absorbs moisture when in contact with a wet surface or tissue, temporarily sticking to the tissue in the process.

Chemicals called NHS esters are mixed in. They can bind with bodily proteins to form stronger bonds. A long-lasting hydrogel kept the tape’s shape stable for over a month — long enough for a typical gut injury to heal.

The non-sticky top layer keeps the patch from attaching to surrounding tissue. This is made from a biodegradable polyurethane that has about the same stretch and stiffness of natural gut tissue.

“We don’t want the patch to be weaker than tissue because otherwise it would risk bursting,” explains Yuk. “We also don’t want it to be stiffer because it would restrict the peristaltic movement in guts that is essential for digestion.”

Innovative patch performed well in animal tests

In experiments, the patch rapidly stuck to large tears and punctures in the bowel, stomach and intestines of rats and pigs. It binds to tissues within a few seconds, and holds for over a month. It is expands and contracts with a functioning organ as it heals.

Afterwards, the patch gradually degrades without causing inflammation or sticking to surrounding tissues. Dr Yuk and colleagues hope it will one day be stocked in operating rooms – as an everyday tool.

Three years ago they designed a similar double-sided sticky tape that joined two wet surfaces together. Surgeons advised a single-sided product might make a more practical impact.

“In practical situations, it’s not common to have to stick two tissues together – organs need to be separate from each other,” says co-lead author Dr. Jingjing Wu. “One suggestion was to use this sticky element to repair leaks and defects in the gut.“

Sewing surgical sutures requires precision and training. Scarring and tearing can cause blood poisoning or sepsis.

“We thought, maybe we could turn our sticky element into a product to repair gut leaks, similar to sealing pipes with duct tape,” adds Yuk. “That pushed us toward something more like single-sided tape.”

In initial tests, the patch did stick to tissues, but it also swelled, just as a fully wet, hydrogel-based nappy would. This swelling stretched the tape and the underlying tear it was intended to seal.

“It was almost an impossible problem because hydrogel naturally swells. But we did a simple trick. We pre-stretched the adhesive layer a bit, then introduced the nonadhesive layer, so when applied to a tissue, that pre-stretching cancels out the swelling,” says Yuk.

The patch was placed in a culture with human epithelial cells that line the surface of organs. They kept growing, demonstrating biocompatibility. When implanted under the skin of rats, the device disappeared after about 12 weeks with no side effects.

The researchers also applied the patch to defects in the animals’ bowels and stomachs. They found it maintained a strong bond as the injuries fully healed. It produced minimal scarring and inflammation compared to sutures.

The patch was further tested on colon defects in pigs, which continued to feed normally. They did not develop fever, lethargy or other adverse health effects. After four weeks the defects fully healed with no sign of secondary leakage.

Results show the surgical patch could potentially safely repair gastrointestinal injuries. It could be applied just as easily as commercial duct tape, said the researchers. They are further developing it through a new startup and hope to pursue FDA approval for human trials.

“We are studying a fundamental mechanics problem, adhesion, in an extremely challenging environment – inside the body,” says project supervisor Professor Xuanhe Zhao. “There are millions of surgeries worldwide a year to repair gastrointestinal defects. The leakage rate is up to 20 percent in high-risk patients. This tape could solve that problem and potentially save thousands of lives.”

The research paper detailing the material is published in Science Translational Medicine.

South West News Service writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.