Even if our taste buds can’t, our gut can sense the difference between real sugar and sugar substitutes. And it’s not just about flavor – intestinal cells are able to distinguish between the two on a molecular level. These microbes then send the message to the brain in milliseconds, researchers say.

Even after scientists found, and attempted to remove, the sweet taste receptors in mice years ago, they were surprised to discover they could still detect and prefer the real sugar over the fake one.

Gut Cells, Sugar, and the Brain

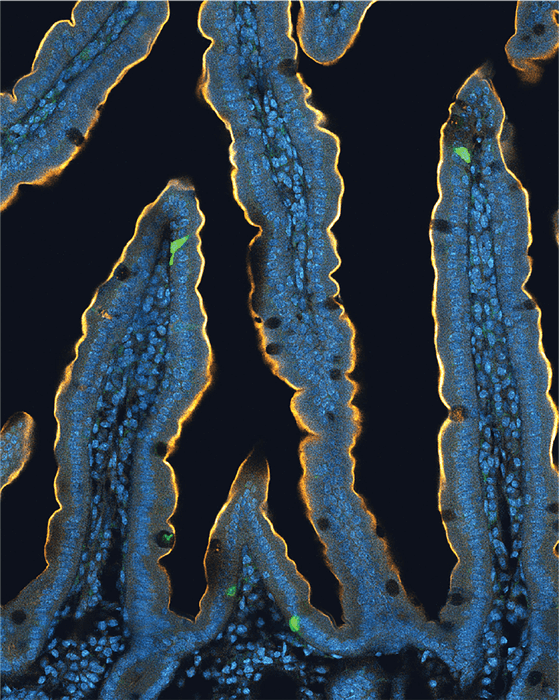

According to an experimental study led by Diego Bohórquez, the reason behind this mystery is way down in the digestive tract. In a statement, Bohórquez says that the cells that sense this difference are in the higher parts of the gut and that injecting sugar directly into the lower levels of the colon or lower intestine does not have the same result. He adds that the gut speaks directly to the brain and changes how we eat.

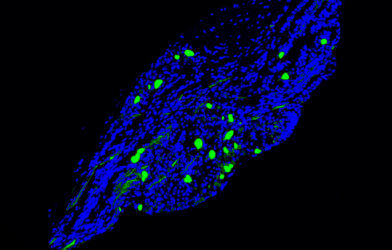

The discovery of a gut cell called the neuropod is driving the research team to keep investigating the crucial part this cell plays as a link between what is in the gut and the influence it has on the brain. The results of this research could have an impact on the future development of new treatments for diseases.

The latest findings of the study further indicate that similarly to taste buds and the tongue or the color-sensing cells in the eye, neuropods are sensory cells of the nervous system. The team’s study shows that these cells not only produce slow hormone signals, they also produce fast neurotransmitter signals that rapidly reach the brain.

“These cells work just like the retinal cone cells that are able to sense the wavelength of light,” Bohórquez says. “They sense traces of sugar versus sweetener and then they release different neurotransmitters that go into different cells in the vagus nerve, and ultimately, the animal knows ‘this is sugar’ or ‘this is sweetener.’”

Test Methods and Future Research

To conduct the testing, lab-grown mouse and human cells represented the small intestine and the upper gut. The scientists showed that upon introduction, real sugar released different neurotransmitters than artificial sugar did.

Using a flexible fiber, the researchers then turned the neuropod cells on and off in the gut of a live mouse to see if the preference for real sugar was due to signals from the gut. When the neuropods were off, there was no clear preference for real sugar.

“We trust our gut with the food we eat,” Bohórquez says. “Sugar has both taste and nutritive value and the gut is able to identify both.” Diego Bohórquez is an associate professor of medicine and neurobiology in the Duke University School of Medicine.

“Many people struggle with sugar cravings, and now we have a better understanding of how the gut senses sugars (and why artificial sweeteners don’t curb those cravings),” says co-first author Kelly Buchanan. “We hope to target this circuit to treat diseases we see every day in the clinic.” Kelly Buchanan is a former Duke University School of Medicine student who is now an Internal Medicine resident at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Future studies by Bohórquez will show how these neuropod cells also recognize other macronutrients. “We always talk about ‘a gut sense,’ and say things like ‘trust your gut,’ well, there’s something to this,” Bohórquez says. “We can change a mouse’s behavior from the gut.” This gives lots of hope for future therapies that focus on gut health.

His team’s study can be found in Nature Neuroscience.