The intestine is part of the human body’s total immune system, but it was discovered recently that the intestine also has its own immunologic memory, fighting reinfection from previous diseases. It protects the body especially from pathogens that invade the mucosa (the lining of the intestine). Scientists at the Institut Pasteur discovered innate effector cells active in early infection that can also be trained to “remember” that disease and protect the host from reinfection.

The organism Escherichia coli is a major cause of intestinal diseases and gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. It is found in drinking water and food, causing diarrhea associated with intestinal inflammation. E. coli is the cause of 9 percent of child deaths in the world. It is a huge public health problem for which greater understanding is needed.

The GI mucosa combats disease-causing organisms while allowing microorganisms to live which are essential for normal body functions. This complex system of adaptive cells provides the earliest defense against infection, then develops memory of the infectious agent by activating specific receptors on B and T lymphocytes. These cells cause production of antibodies and inflammatory substances. It is still to be determined how the effector cells which constitute the innate immune system provide tolerance of pathogens and protection of the mucosal barrier.

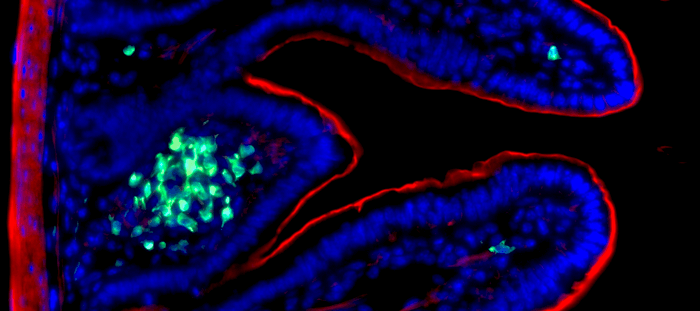

Scientist James Di Santo, who leads the research at the Institut Pasteur, describes a new type of lymphocytes (ILC3s), different from the B and T lymphocytes, that have an essential role is the innate immune response. These are especially active in the GI mucosa, where they produce inflammatory cytokines. These cytokines produce antimicrobial peptides, which reduce the bacterial load to protect the intestine’s barrier function.

The ILC3s persist for months, in an active state after exposure to a pathogen. In a second infection, these “trained” ILC3s can control infection by enhanced production of cytokines and antimicrobial peptides.

“Our research demonstrates that intestinal ILC3s acquire a memory to strengthen gut mucosal defenses against repeated infections over time,” explains Nicolas Serafini, first author on the study, in a statement.

“The ability to train the innate immune system in the mucosa paves the way for improvements to the body’s defenses against a variety of pathogens that cause human diseases,” Di Santo adds.

This discovery could lead, long-term, to new therapies to treat intestinal diseases, such as inflammatory bowel diseases or cancer.

The paper is published in the journal Science.