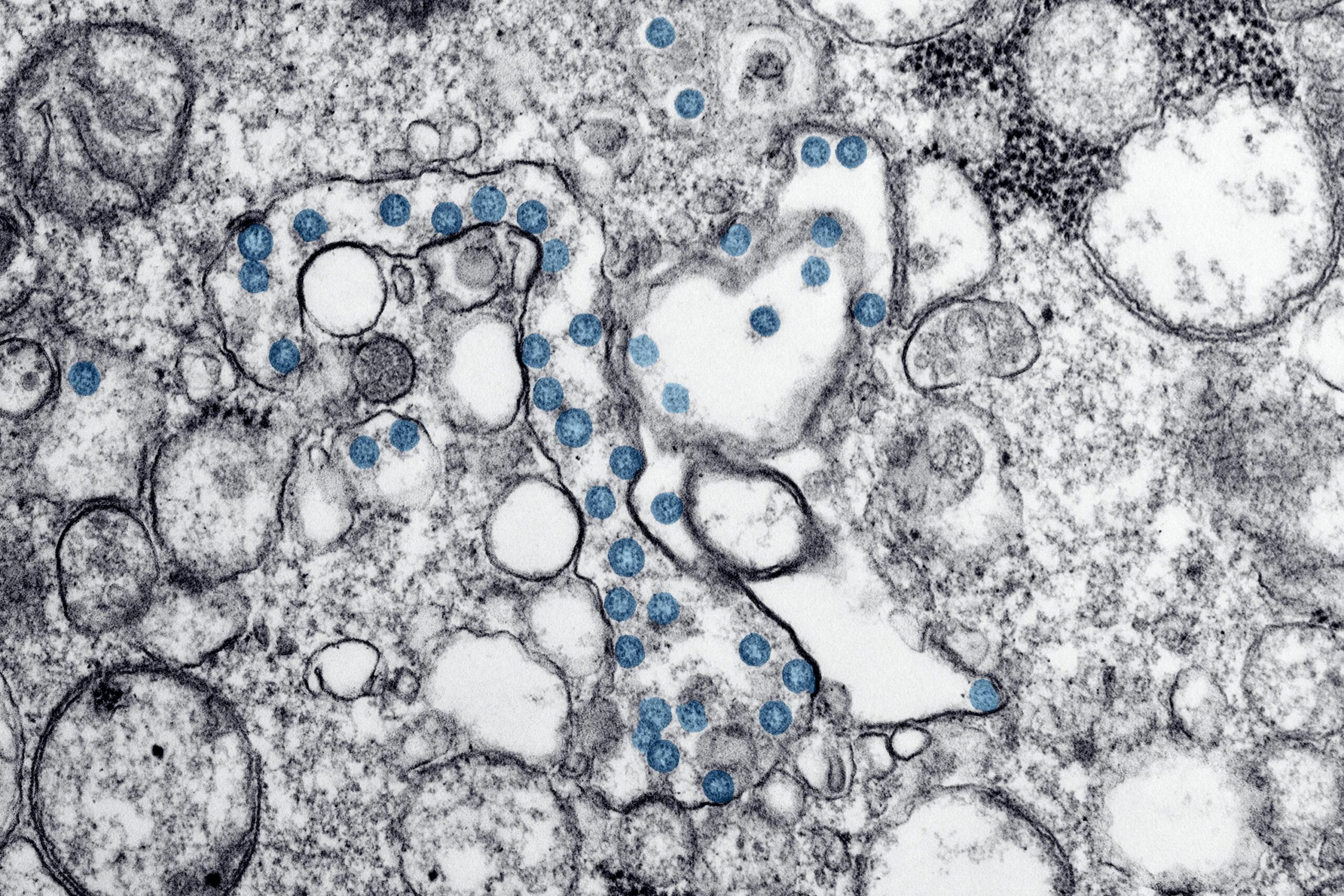

The bacterium Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) causes more than just an upset stomach. It triggers gastric inflammation, increasing the risk of stomach cancer. Understanding how the bacteria works could help scientists know how to disrupt it and potentially prevent stomach cancer in the process.

For a microscopic bacteria, H. pylori has infected almost half the world’s population. It is one of the causes of chronic bacterial infections in humans, though how it causes so much damage remained poorly understood.

“Until now, researchers had assumed that a Helicobacter infection causes direct damage to the gastric gland cells in the stomach lining and that gastric pathology upon infection is simply the result of this process,” explains Dr. Michael Sigal, professor of translational gastrointestinal oncology at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin and senior author of the study in a statement. “In fact, our team has now discovered that the infection disrupts complex interactions between different cell types and signals which are responsible for tissue stability.”

H. pylori may cause inflammation of the stomach by leaving the protective lining inside the tissue exposed to stomach acid. The disintegration from stomach acid means the stomach lining has to regenerate every few weeks, prompting increased cell division. The inflammation from the bacteria, however, deactivates the protective mechanism that restricts cell division in healthy stomach tissue cells as well, causing uncontrolled proliferation of cells.

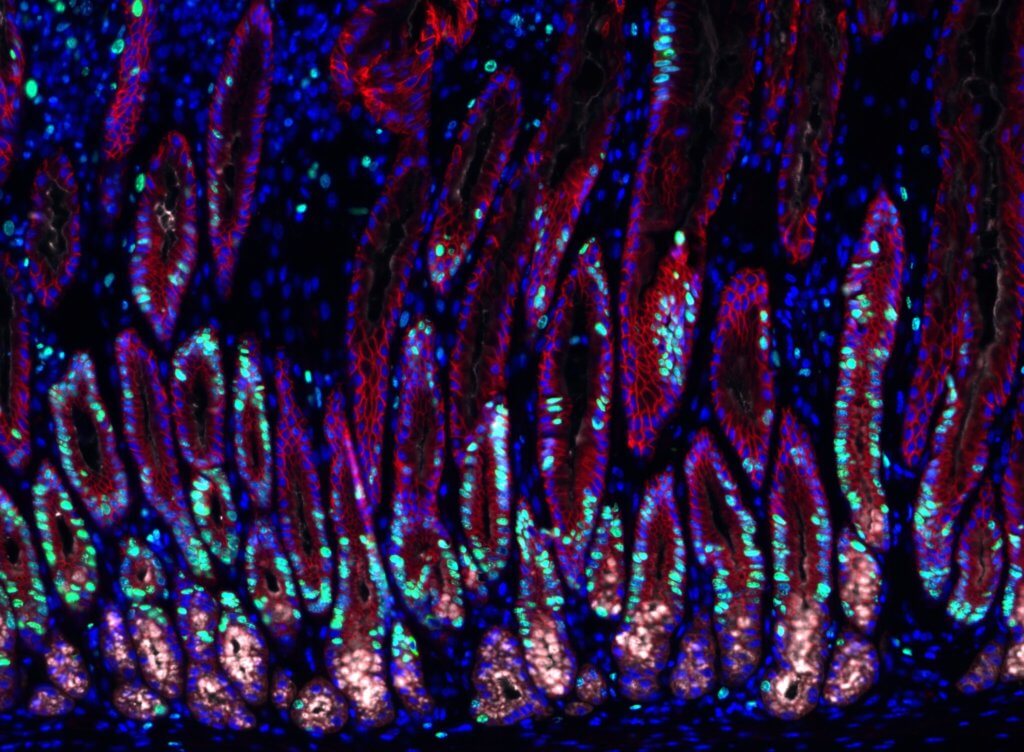

To make these discoveries, the team used mouse models to study changes inside the gastric glands. They isolated a few gastric gland cells to observe in detail. To avoid using more animals, the team constructed organ-like tissue microstructures called organoids. The microscopic stomach recreated many of the gastric glands’ characteristics, allowing researchers to look at the signaling effect on the stem cells inside of gastric glands.

Stromal cells, a type of cell around the gastric glands, were once thought to be essential for stabilizing the glands. But the team also observed their role in making signaling molecules that influence gland cell behavior. One of the signaling molecules was bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) which are often involved in tissue development. When stromal cells surrounding the glands block the BMP signaling pathway, it stimulated the growth of surrounding stem cells. But when stromal cells at the gland surface activated the signaling pathway, it blocked cell proliferation.

H. pylori disrupts the stability stromal cells confer to the stomach. When present, the bacterial infection releases pro-inflammatory cytokines called interferon-gamma. The infection-driven inflammatory response messes with BMP signaling activity and, by blocking it, it triggers cell growth. The uncontrolled cell growth may cause hyperplasia, a precancerous lesion that’s associated with enlarged tissue.

“In addition to their well-characterized antimicrobial effects, pro-inflammatory substances such as IFN-γ affect both cell proliferation and tissue stem cell behavior and therefore have a direct impact on tissue homeostasis. In the case of tissue damage, increased cell proliferation can be useful, as it promotes rapid healing. In the case of chronic inflammation associated with a Helicobacter infection, however, it could facilitate the development of precancerous lesions,” explains Dr. Sigal. Gaining a better understanding of the delicate balance controlling cell growth could apply to other organs and could provide a new treatment target for both cancer prevention and regenerative medicine.

The study is published in Nature Communications.