A mouse study from the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine shows that adding the Helicobacter hepaticus bacterial species to the gut microbiome can ramp up a strong immune response against colon cancer cells. The findings could use gut microbes as a future medicine for treating advanced colon cancer tumors resistant to current drug and immune therapies.

Colorectal cancer is a deadly disease that has a poor response to immunotherapy because the tumor can change its microenvironment and escape recognition by the immune system. Because of this, doctors rely on surgeries, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, which have several uncomfortable side effects.

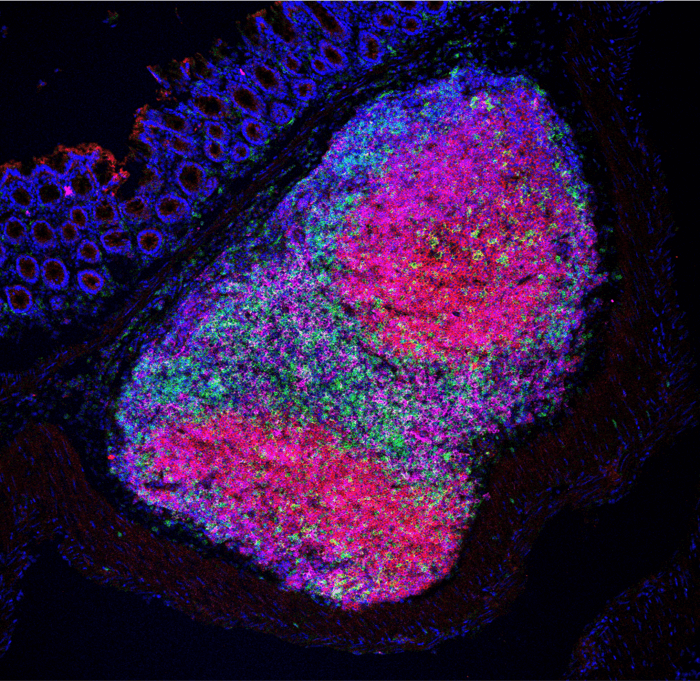

This bacterial species helped the adaptive immune system by activating Helper T cells and antibody-producing B cells. The expanded immune response causes shrinkage in colon tumors and increased the survival of mice.

“Altering the gut microbiome doesn’t have to rely on serendipity to get a therapeutic advantage,” says Timothy Hand, PhD, assistant professor of immunology at Pitt and corresponding author in a press release. “Instead of using fecal transplants and hoping to get the right microbial composition, we now are much better positioned to develop effective drugs designed based on molecules produced by beneficial bacteria.”

The study involved infecting mice with colon cancer and then inserting the H. hepaticus bacteria into their guts. H. hepaticus is associated with strong immune responses and lives around the thick mucus making up the gut barrier.

Insertion of H. hepaticus significantly decreased the number and size of tumors as well as increased the mice’s lifespan. They connected the reduction in tumor growth to a boost in Helper T cells, B cells, and natural killer cells to the tumor site. The bacteria was also connected with the formation of highly organized structures that created a favorable environment for immune cell maturation.

“Ignoring the influence of gut bacteria on the success of cancer therapies seems like a massive oversight,” said lead author Abigail Overacre-Delgoffe, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Pitt’s Department of Pediatrics and Damon Runyon Fellow. “We need to think about all the things that patients go through day to day that can cause treatments to succeed or fail. We can’t ignore the bacteria anymore—they influence everything.”

The study is published in the journal Immunity.