Despite living far apart, the gut and the brain are in a very close long-distance relationship. Their constant communication helps in regulating immunity, mental health, and more. Now researchers from Northern Arizona University are examining how their connection could contribute to the onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s disease is one form of dementia that causes severe cognitive impairments. Almost 6.2 million Americans have Alzheimer’s and experience trouble with memory, thinking, and carrying out daily life functions. While some treatments could help improve the quality of life for those with Alzheimer’s, there is no cure.

The current research focus is then to prevent Alzheimer’s from happening in the first place and to do that, three scientists are looking into potential causes behind it, including gut bacteria. Gut bacteria have stood out for their effect on the brain, though how it affects Alzheimer’s is poorly understood.

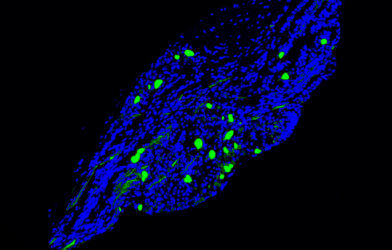

The research, which recently received a $418,000 grant from the National Institute of Health’s National Institute of Aging, focuses on the gut microbiome dynamics to Alzheimer’s progression and neuroinflammation. The team will use quantitative stable isotope probing (qSIP), a new tool in microbial research to look at the growth of bacterial species in mice models of Alzheimer’s.

“Our goal is to use a technique that was developed in soil microbial ecology (qSIP) to understand the dynamics of the microbiome in health sciences. Previous studies of human gut microbiomes show differences in the microbes that are present in individuals with AD compared to age-matched healthy participants,” explains Emily Cope, an assistant professor and one of the scientists awarded the grant in a press release. “Studies in mice also show that mice with certain characteristics of AD have alterations in their gut microbiome. These studies support the idea that the gut microbiome may play a role in Alzheimer’s disease progression, these studies, and our prior studies, use a technique that is good at telling us which microbes are present, but cannot reveal which microbes are actively growing in an environment.”

For example, if they could show that certain bacteria are dividing faster than others when there are signs of Alzheimer’s such as amyloid-beta plaques and tauopathy, it could determine gut microbes role in protecting or instigating disease.

“We also want to know if this method is better at predicting amyloid-beta plaque abundance and tauopathy than standard microbiome sequencing methods. We expect that we will be able to identify rare microbes that are growing quickly in mice modeling AD that would have been missed using standard methods. If we do, we can target these microbes in future studies to determine exactly how they influence brain health,” Dr. Cope says.

The qSIP technology was first developed at Northern Arizona University and used to calculate the growth rates of bacteria in forest soils. The current research project will extend its application to studying mice gut microbiomes and potentially answer questions in medical microbiology.