The Human Genome Project was, arguably, the greatest feat of scientific exploration in history. It identified, in sequence, all three billion DNA letters in the genetic makeup of a human. Also astonishing – the project was completed two years ahead of schedule and under budget! The scientific exploration continues. Scientists at Cornell University are developing novel methods of data processing and changing their focus of interest to study how human genetics shape the gut microbiome and its functions.

Ilana Brito, assistant professor, Nancy E. and Peter C. Meinig School of Biomedical Engineering, and her team developed the new method to examine host-microbiome genetic interactions. There were many instances in which a human host’s genetic makeup affected the functioning of the gut microbiome.

“When a disease or phenotype is caused by a single genetic mutation it can be a relatively straightforward process to find the gene responsible,” Brito explains in a statement. Just as often, however, a suite of genes interact to result in disease or other phenotypic expression. There are many sequential variations from person to person, and within paired chromosomes of the same person.

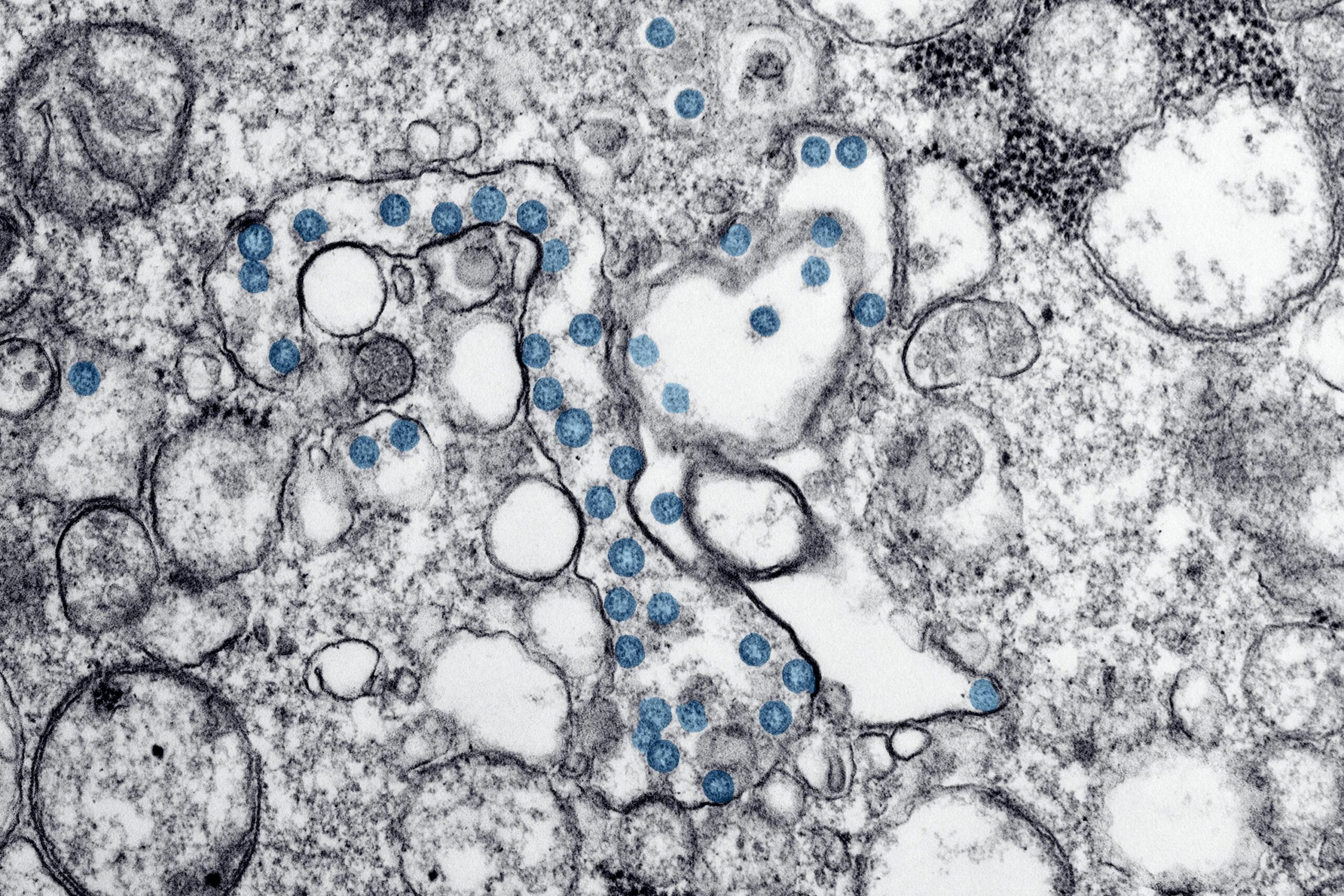

A variation produced by the substitution of a single nucleotide is described as a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP). Brito’s team was able to identify SNPs that correlated with microbiome-associated traits, disorders and cancers. In other words, they were able to show direct effects of the human genome on the functions of the gut microbiome.

“Associating variation in the human genome with the variation in the gut microbiome has been tricky, because the species of bacteria in the gut are also not independent of each other,” said Professor Andrew Clark, Molecular Biology and Genetics, Cornell.

Their study was novel in that It focused on the function of the gut microbiome as opposed to the genetic makeup of each species in the agglomeration of organisms that forms the microbiome. They looked at broad collections of human genes and their effect on the functions of the microbiome as opposed to examining single genes, and used a new strategy to model the distribution of functions and species within the human gut.

Past models were not a good fit for the characteristics common to metagenomic sequencing data sets. Professor Martin Wells, Department of Information Science, Cornell, introduced the idea of using the Tweedie distribution – a type of probability modeling – to account for these characteristics.

The study is published in the journal Nature.