As complications related to antibiotic resistance continue to arise, it’s become increasingly important to develop clinical methods that can help combat it. A group of international researchers have developed a more earth-friendly and effective approach for altering antibiotics. They believe their method will make the medications stronger against drug-resistant bacteria by using microorganisms that produce the necessary compounds naturally.

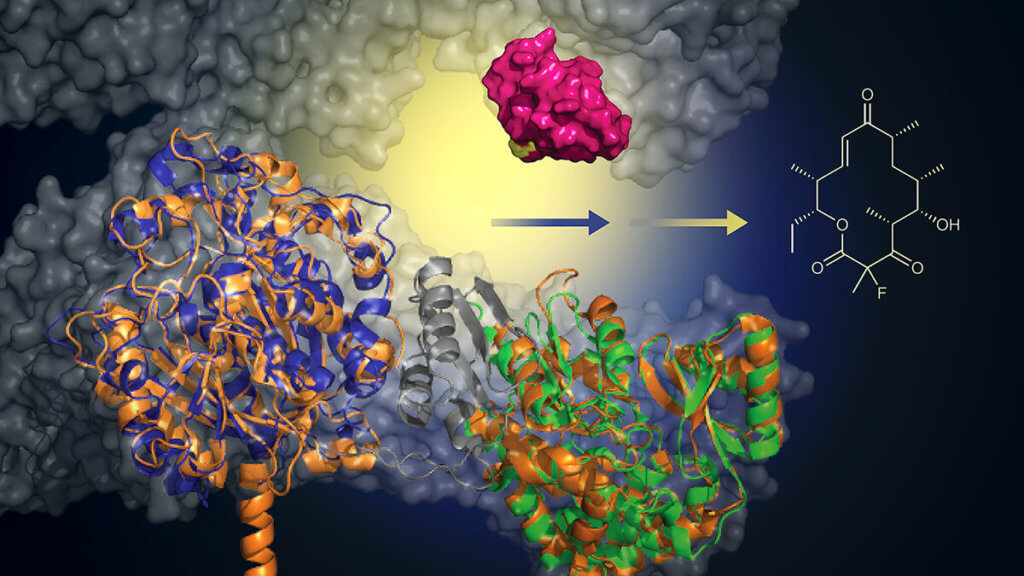

To begin, the team used a microorganism that is genetically designed to produce the antibiotic erythromycin. German scientists wondered if they could alter this to generate the same antibiotic, but with one additional fluorine atom. By adding this, it would help to make it more suitable for pharmaceutical practices.

“We had been analyzing fatty acid synthesis for several years when we identified a part of a mouse protein that we believed could be used for directed biosynthesis of these modified antibiotics, if added to a biological system that can already make the native compound,” says Martin Grininger, professor for biomolecular chemistry at Goethe University, in a statement.

Erythromycin works by binding to and inhibiting the ribosomal activity of a bacteria, which is crucial for its survival. The concern is that many bacteria have evolved in such a way that prevents this binding, making them resistant to antibiotics. By manipulating the antibiotic’s structure with an additional fluorine atom, this could act to overtake this evolutionary development, allowing the compound to fight off bacteria again.

Usually, adding fluorine is tedious and requires toxic chemicals to encourage the reaction. The team was able to develop a new biosynthetic method that alleviates these limitations, making it a promising choice. “It’s a very exciting development, because we can bypass all the time-consuming synthetic steps and dangerous chemicals,” says David Sherman, a faculty member at the University of Michigan Life Sciences Institute and professor of medicinal chemistry in the College of Pharmacy.

It’s estimated that around 47 million antibiotic courses are prescribed yearly in the United States for conditions that don’t even require them, meaning that they are often loosely and unnecessarily given to patients. As such, the fact that these findings have the ability to provide a basis for more in-depth research efforts to develop effective antibiotics against resistant bacteria is more than ideal.

In the same voice, the researchers strongly believe that fluorinated compounds still have ways to go before they’re used in clinical settings. As the work continues to make way, the biosynthetic development may even expand for use as less toxic in antivirals and cancer treatments.

This study is published in the journal Nature Chemistry.