For decades, we’ve been told that the human gut is a simple, uniform tube—a straightforward conveyor belt for food. It’s an easy idea to grasp, and for a long time, it’s been the foundation of how we think about gut health. But what if that idea is completely wrong? What if your gut isn’t a single, consistent environment, but rather a series of distinct neighborhoods, each with its own unique community of bacteria and immune defenses? A groundbreaking new study published in the journal Gut Microbes reveals that the specific microbes living in a particular segment of your gut directly shape the immune system in that exact same spot. This discovery challenges our long-held assumptions and suggests that to understand and treat diseases like Crohn’s or allergies, we might need to stop looking at the gut as a single entity and start looking for the specific “hotspot” where the problem is actually happening.

Unlocking the Secrets of a Segmented System

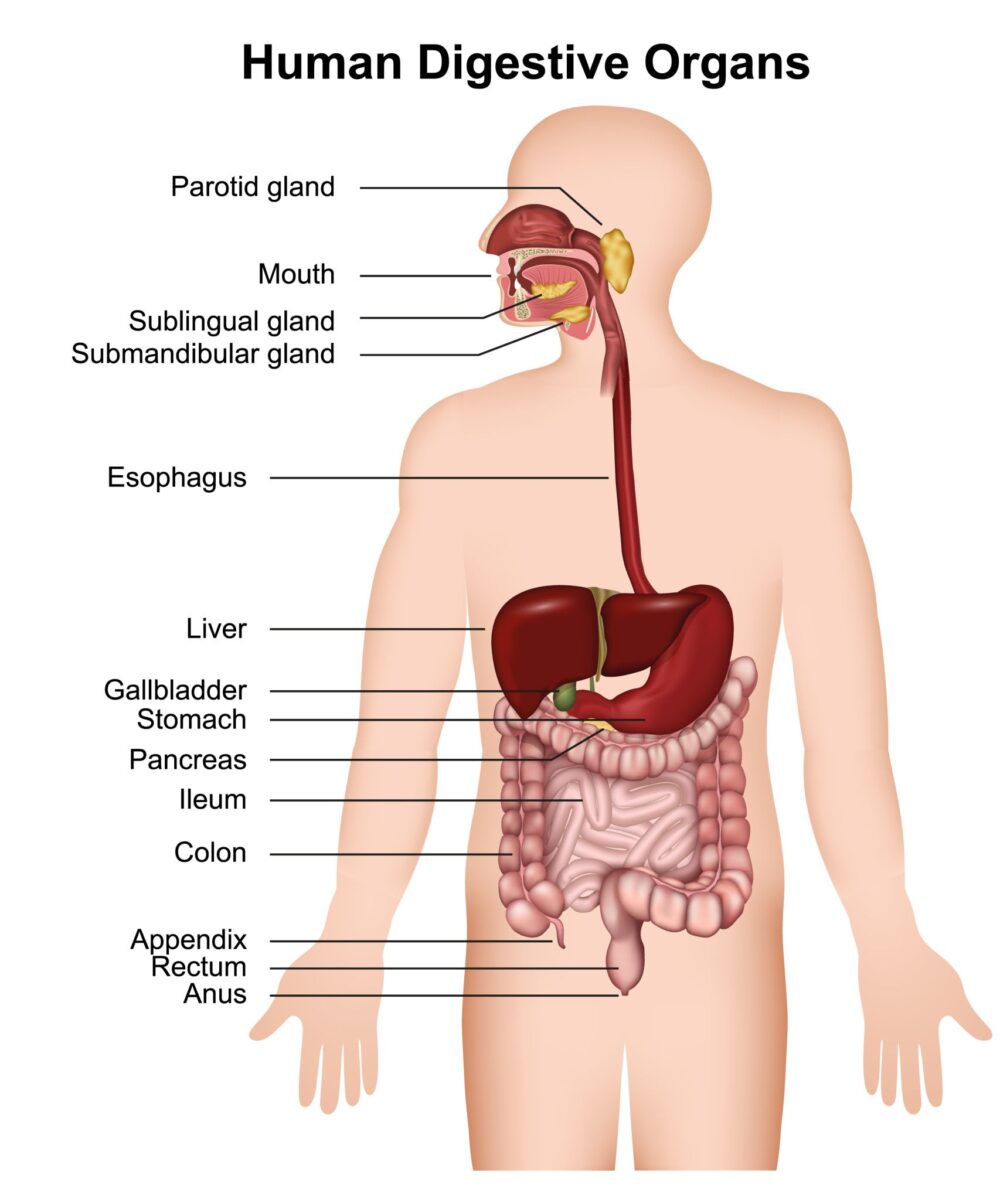

To uncover this segmented world, researchers designed a study comparing two groups of mice. The first group was raised in a sterile, germ-free (GF) environment, meaning their digestive systems were completely devoid of any bacteria. The second group, called conventionally colonized (CONV) mice, had a normal, healthy gut microbiome. The team then did something unprecedented: they dissected the entire intestines of both groups into five distinct sections to analyze the microbes and immune cells in each part. To understand the bacteria, they used a technique that let them identify all the different types and their numbers. To study the immune cells, they used a method that allowed them to count and identify different cell types, essentially creating a census of the immune system in each gut segment. The study was small, with only six mice in each group, but the detailed analysis of each segment provided a wealth of information.

Your Gut’s Unique Neighborhoods

The results were a complete remapping of the gut. In the mice with a normal microbiome, the immune system was far from uniform. The upper part of the small intestine was teeming with what are called innate immune cells—the body’s first line of defense. But as the researchers moved to the large intestine, the proportions flipped. Innate cells became a smaller part of the population, and adaptive immune cells—the more specialized soldiers of the immune system—took over.

This sophisticated, segmented arrangement was entirely missing in the germ-free mice. Without any bacteria to interact with, their immune system lacked this advanced organization. This finding confirms the idea that the microbiome isn’t just a passenger in our gut; it’s an architect of our immune system, actively shaping its structure and defenses. Another finding also revealed that in the conventional mice, the immune profiles of each animal were more unique from one another than in the germ-free mice. This suggests that your specific microbial community creates a distinct, personalized immune profile, making your gut truly one-of-a-kind.

The study also confirmed that the microbial communities themselves are not uniform. The number and variety of bacteria exploded from the upper to the lower parts of the intestine. While the large intestine had the greatest number of species, a small core group of 72 bacterial species was found to be consistently present throughout the entire digestive tract. These persistent few species make up a crucial foundation of the gut microbiome.

What This Means for Your Health

This research is more than just a biological curiosity; it’s a powerful new framework for understanding health and disease. It moves us away from the outdated, one-size-fits-all approach to gut health and forces us to look at the digestive tract as a complex series of interconnected but distinct environments. The discovery gives us new clues about why certain diseases, like Crohn’s, affect specific areas of the gut, and why dietary changes might have different effects on different parts of our digestive system. The path forward for scientists and doctors is clear: we must now begin to unravel how these segmented microbial and immune communities function in humans to create more targeted and effective treatments.

Paper Summary

Methodology

Researchers compared two groups of mice—one with a normal microbiome and one raised in a sterile, germ-free environment. The intestines were divided into five segments, and advanced sequencing and cell-counting methods were used to characterize the bacterial communities and immune cells in each section. The study used a small sample size of six mice in each group.

Results

The study found a distinct pattern in the guts of mice with a microbiome. Both the types of microbes and immune cells changed significantly from the upper to the lower intestine. This segmental organization was absent in the germ-free mice, indicating that the microbiome is responsible for creating this unique immune structure. The findings also showed that each conventional mouse had a more personalized and varied immune profile compared to the germ-free mice.

Limitations

The study was conducted on a small sample of mice (n=6 per group), which may not fully represent the complexity of the human digestive system. Further research in humans is needed to confirm these findings.

Funding and Disclosures

The research was conducted at the Experimental and Clinical Research Center of Max Delbrück Center and Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin. The paper is an open-access article.

Publication Information

The paper, titled “Segmental patterning of microbiota and immune cells in the murine intestinal tract,” was published in the journal Gut Microbes on September 10, 2024. The DOI is 10.1080/19490976.2024.2398126.