What if a simple change in your gut could warn you about a concussion, even before you feel the typical symptoms? For years, the focus after a head injury has been on what’s visible – the dizzy spell, the headache, the feeling of fogginess. But new research is turning that idea on its head, suggesting that the vast community of microbes living in our digestive system might hold a crucial clue to better understanding and diagnosing concussions. This fresh perspective could transform how we protect athletes, particularly those in high-impact sports like football.

A recent pilot study, published in Brain, Behavior, & Immunity – Health, explores the surprising connection between brain trauma and gut health. It hints that changes in the gut’s microscopic environment could act as an early indicator for concussions. For collegiate football players, a group constantly at risk of head impacts, this discovery could revolutionize detection and management, paving the way for quicker, more accurate diagnoses and ultimately, safer futures. The idea that your gut bacteria could sound an alarm, before clear symptoms even appear, is a powerful and potentially life-changing prospect.

Unpacking the Brain-Gut Connection in Athletes

Researchers set out to investigate the “brain-gut axis,” a two-way communication pathway between the brain and the digestive system. While severe brain injuries are known to affect the gut, the impact of milder, sports-related concussions on this axis has largely been a mystery. This study aimed to shed light on that unknown.

The research team enlisted 33 male collegiate football players, aged 18 to 23, from a major university. This group included a diverse mix of athletes: about 39.4% identified as Black, non-Hispanic; 54.5% as White, non-Hispanic; and 6.1% as Mixed, with 18.2% also identifying as Hispanic. Importantly, none of the players had pre-existing conditions that might affect their brain function or gut health.

Samples of stool, blood, and saliva were collected from these athletes at three key points during their season: mid-season, post-season (after their last game), and off-season (after a resting period). Crucially, additional samples were collected within 24-48 hours from four athletes who received a diagnosed concussion during the study period.

Gut Microbe Shifts: A Post-Concussion Signature?

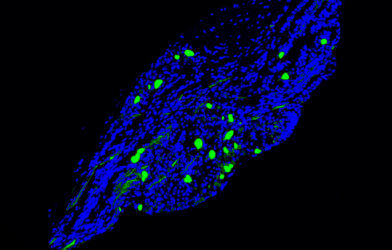

The core of the study involved a detailed analysis of the gut microbiome – the trillions of bacteria and other tiny organisms living in our intestines – using advanced genetic techniques. The findings were striking. In the athletes who suffered a diagnosed concussion, there was a noticeable drop in the numbers of two specific gut bacteria: Eubacterium rectale and Anaerostipes hadrus. Both of these belong to the Lachnospiraceae family and are known for producing butyrate, a beneficial substance vital for a healthy gut. The paper notes that “butyrate-producing bacteria have been proposed as next-generation probiotics, due to their potential role as health-promoting agents counteracting disease-related shifts in the gut microbiome.”

Conversely, seven other types of bacteria, including Ruminococcaceae bacterium CPB6, Mageeibacillus indolicus, and Bacillus cereus, were found in greater numbers in the concussed group. While the study didn’t find significant changes in the mouth’s microbiome, these alterations in gut bacteria following a concussion present an exciting new path for research and diagnosis.

Beyond these bacterial shifts, the study also looked at markers of inflammation in the blood. Two specific markers, S100β and SAA, showed a positive connection with the abundance of Eubacterium rectale in athletes who did not experience a concussion during the season. This connection between these blood markers and a specific gut bacterium is important because brain inflammation is a known factor in both the immediate and long-term effects of head trauma.

The Unseen Impacts and Future of Concussion Detection

These findings suggest a future where a simple stool test could become an important tool in concussion diagnosis. Current concussion assessments often rely on symptoms reported by the athlete and clinical evaluations, which can be tricky since many concussions go unrecognized or aren’t reported. The prospect of a biological marker in the gut offering an objective measurement is incredibly promising.

It’s important to remember that this was a pilot study with a limited number of concussed athletes. The researchers emphasize the need for larger studies to confirm these findings and explore additional factors, like player position and diet, which could also affect gut health and concussion risk. The paper states that “larger longitudinal studies are needed to confirm these preliminary findings and to determine if specific changes in the gut microbiome are reliably associated with concussive injury.” Despite its size, this study represents a significant step towards understanding the full impact of concussions on an athlete’s entire body. If changes in gut bacteria can indeed signal a brain injury, it could lead to earlier interventions, more personalized treatments, and ultimately, a safer environment for athletes in contact sports. The conversation about concussions is clearly expanding beyond just the head; it’s about the entire interconnected human system.

Paper Summary

Methodology

This pilot study involved 33 male collegiate football players. Blood, stool, and saliva samples were collected mid-season, post-season, and off-season, with additional samples from four concussed athletes. Stool and saliva samples were analyzed for microbiome changes using genetic sequencing, and blood samples were used to measure inflammatory markers.

Results

The study found decreased Eubacterium rectale and Anaerostipes hadrus and increased seven other bacterial species in concussed athletes’ gut microbiomes. No significant changes were found in the oral microbiome. Serum GFAP levels increased during the season, and serum S100β and SAA levels correlated with Eubacterium rectale in non-concussed athletes.

Limitations

Key limitations include a small sample size for concussed athletes, limiting statistical power. The absence of a pre-season baseline sample was also noted. Future research requires larger studies, and consideration of factors like player position, detailed diet, and objective head impact measurements.

Funding and Disclosures

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), the Institute of Biosciences and Bioengineering (IBB) Hamill Innovation Award, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), and Houston Methodist Research Institute funds. Authors declared no competing interests.

Publication Information

The study, titled “Alterations to the gut microbiome after sport-related concussion in a collegiate football players cohort: A pilot study,” was published in Brain, Behavior, & Immunity – Health, Volume 21 (2022), article number 100438. The corresponding author is S. Villapol.