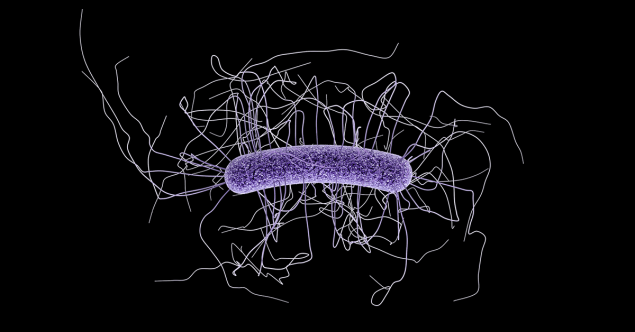

The incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) in Americans younger than 50 years has been rapidly increasing. The cause, or causes, of this alarming trend is obscure, and the subject of considerable, vigorous investigation. Research from the Kimmel Cancer Center and the Bloomberg~Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine suggests that Clostridium difficile (C. diff), may contribute to this trend in earlier-onset colorectal cancer.

“The uptick of individuals under age 50 being diagnosed with colorectal cancer in recent years has been shocking. We found that this bacterium appears to be a very unexpected contributor to colon malignancy, the process by which normal cells become cancer,” says study co-author Dr. Cynthia Sears, a professor of cancer immunotherapy and medicine at the school, in a statement.

Sears and several colleagues at Hopkins instilled bacterial samples in mice to determine whether a single bacterial species, or a community of bacteria, were promoting tumor formation. Toxigenic C. diff, (the type usually associated with diarrhea in humans), was absent in mice which did not develop tumors, but was present in mice which developed tumors. When the researchers added this bacterium to the samples that originally did not cause tumors, it induced colon tumors in the mice. Additional tests showed that C. diff alone prompted tumor formation in the animal models.

Additional investigations showed that C. diff caused changes within colon cells that made them more vulnerable to cancer.

Exposure of colon cells to the toxigenic C. diff triggered genes that induce colorectal cancer. The cells produced unstable, reactive molecules that damage DNA, and they also prompted immune activity associated with inflammation.

According to the researchers, the toxin produced by this bacterium — known as TcdB — seems to cause the colorectal cancer-inducing activity. When they used genetically engineered C. diff strains that contained inactivated toxin genes and/or released a related C. diff toxin called TcdA, mice infected with the TcdB-inactivated microbes produced far fewer tumors than those with TcdB-active microbes. TcdA alone, made by C. diff, was insufficient to cause tumors.

To date, Drewes says, data linking C. diff with CRC in humans is limited. If additional research verifies that a connection exists, however, it could lead to screening for subclinical C. diff infection or previous infection as a risk factor for cancer. Since lengthy exposures to TcdB may increase colorectal cancer risk, prevention could include greater efforts to effectively eradicate the pathogen, which recurs repeatedly in 15-30 percent of patients after initial treatment.

“This link between C. difficile and CRC needs to be confirmed in prospective, longitudinal cohorts. Developing better strategies and therapeutics to reduce the risk of C. difficile primary infection and recurrence could both spare patients the immediate consequences of severe diarrhea and potentially limit CRC risk later on,” Drewes says.

The study is published in the journal Cancer Discovery.