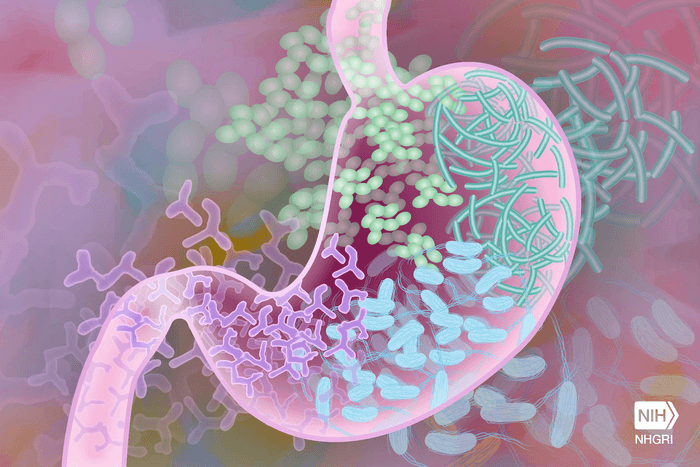

Your gut microbiome may not prevent a COVID-19 infection, but a healthy gut may ward off other viral infections. A recent study by researchers in Sweden discovered how the gut microbiome helps the immune system develop resistance to viruses.

Using mice, the study also reports that suppressing the gut microbiome makes you more prone to systemic viral infections — reaffirming the importance of keeping the gut healthy.

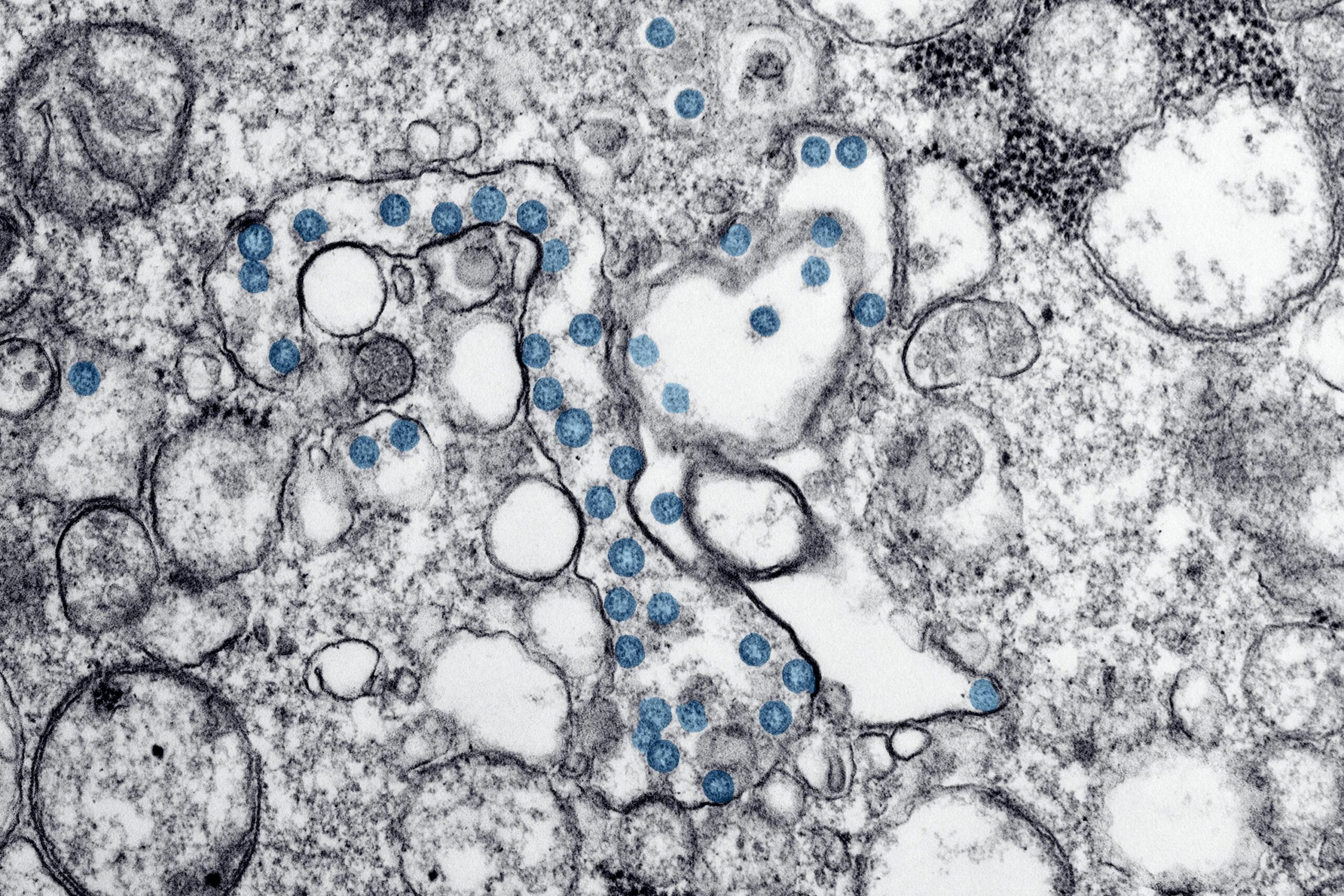

Findings showed that gut microbes release membrane vesicles that lead to the delivery of bacterial DNA to host cells. Exposing host cells to bacterial DNA triggers the activation of the systolic cGAS-STING-IFN-I axis. This activates DNA sensors from the innate immune system. These DNA-binding proteins help detect any abnormal changes in a cell’s DNA and alert the innate immune system to deliver an anti-viral response.

“We were interested in the influence of gut bacteria on viral infections. So, we treated mice with antibiotics and then infected them with two different virus – a DNA virus, herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), or an RNA virus, vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV),” explains lead authorDr. Saskia Erttmann a researcher at Umeå University, in a statement. “We found that antibiotic treatment made mice more susceptible to these viruses and that this was due to a decrease in basal expression of antiviral immune molecules called the type I interferon (IFN-Is)”,

To learn how gut microbes help express IFN-I, they studied mice with weak immune systems. Their study showed that microbial activation of IFN-1 indirectly triggered the activation of the cGAS-STING pathway. Another set of mice that had the cGAS-STING-pathway surgically removed was less responsive to viruses and more likely to become infected with HSV-1 and VSV.

The researchers describe the microbial role in immune activation as surprising because it’s been assumed that toll-like receptors are heavily involved in activating the innate immune system. Additionally, they thought that the activation of cytosolic immune receptors such as cGAS only happened in the presence of DNA viruses, harmful bacteria, or parasites with virus-like qualities.

“Thus, the finding that the intracellular cGAS-STING pathway is a sensor of extracellular gut bacteria was unexpected. Moreover, it was unclear to us how gut bacteria, physically separated from host cells by barriers such as the mucus and gut epithelial layer, are nonetheless able to trigger a systemic cGAS-STING-IFN-I response to protect distal organs against viruses”, explains Dr. Nelson Gekara, a researcher at Stockholm University and the senior study author.

The team proposes that gut bacteria deliver DNA to other cells through bacterial membrane vesicles. These vesicles can travel to different tissues and bypass cell membrane barriers. Therefore, the vesicles released by bacteria help mediate a cGAS-STING-IFN-1 immune response. In the study, they found DNA-containing membrane vesicles from gut microbes in the blood of mice. When cells with bacterial membrane vesicles were injected into mice, they helped to eliminate any present viruses.

Given the importance of gut microbes in activating the first line of immune defense against viruses, the researchers emphasize the risk of antibiotics that can eliminate these beneficial bacteria.

“This study fills an important gap in our understanding of how the gut microbiota mediates systemic immune modulation. They also underscore the under-appreciated risk of antibiotics: antibiotics are commonly taken by self-medicating patients to ‘treat’ undiagnosed illnesses and are sometimes prescribed to patients, as a precaution against bacterial infections that often emerge after viral infection. Our results show that by perturbing the microbiota, antibiotics can adversely impair our ability to fight viral infections. A relevant and perhaps timely message in the current times of a global viral pandemic is that overuse of antibiotics can exacerbate viral infections”, concludes Dr. Nelson Gekara.

The study is published in the research journal Immunity.