Impairment to the brain whether it be from injury or infection can have wide-ranging effects from altering emotions to hampering intelligence and the ability to reason. The physical barriers that encase and protect the brain are evident. However, the complex mechanism by which the brain protects itself from infection has not yet been fully discovered. A recent study suggests a surprising ally in its defense against bacteria and viruses: the gut.

Antibodies and the Meninges

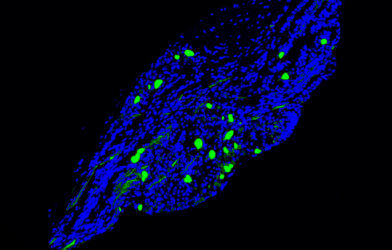

A team led by University of Cambridge scientists and the National Institute of Health recently published research which found that the meninges (watertight tissues wrapping the brain) are home to plasma cells — immune cells that secrete antibodies. Researchers were surprised to find that the specific antibody produced by these cells is normally the type found in the intestine.

The antibodies normally found in the blood are known as Immunoglobulin G (IgG). These protect the inside of the body and are produced in the spleen and bone marrow. The antibodies found in the meninges, however, were Immunoglobulin A (IgA), which are produced in the gut lining or in the lining of the nose or lungs, and protect the mucosal surfaces – those surfaces that interface with the outside environment.

Researchers sequenced antibody genes found in B cells (a type of immune cell that produces plasma cells) and plasma cells in the gut lining and meninges and showed they were related.

“The exact way in which the brain protects itself from infection, beyond the physical barrier of the meninges, has been something of a mystery, but to find that an important line of defense starts in the gut was quite a surprise,” says lead scientist Professor Menna Clatworthy in a statement. Clatworthy is a researcher in the Department of Medicine at the University of Cambridge and the Wellcome Sanger Institute.

“But actually, it makes perfect sense: even a minor breach of the intestinal barrier will allow bugs to enter the bloodstream, with devastating consequences if they’re able to spread into the brain. Seeding the meninges with antibody-producing cells that are selected to recognize gut microbes ensures defence against the most likely invaders,” states Clatworthy.

An Unexpected Connection

Using mice, researchers found that when there are no bacteria in the gut, there are no IgA-producing cells in the meninges.This shows that these cells actually originate in the intestine. When the plasma cells in the meninges are removed, microbes are able to spread to the brain from the bloodstream.

Additionally, the presence of IgA cells in the human meninges was confirmed by analyzing samples taken during surgery. This shows that the defense system is likely to play an important role in protecting humans from brain infections like meningitis and encephalitis.

This study was published in Nature.